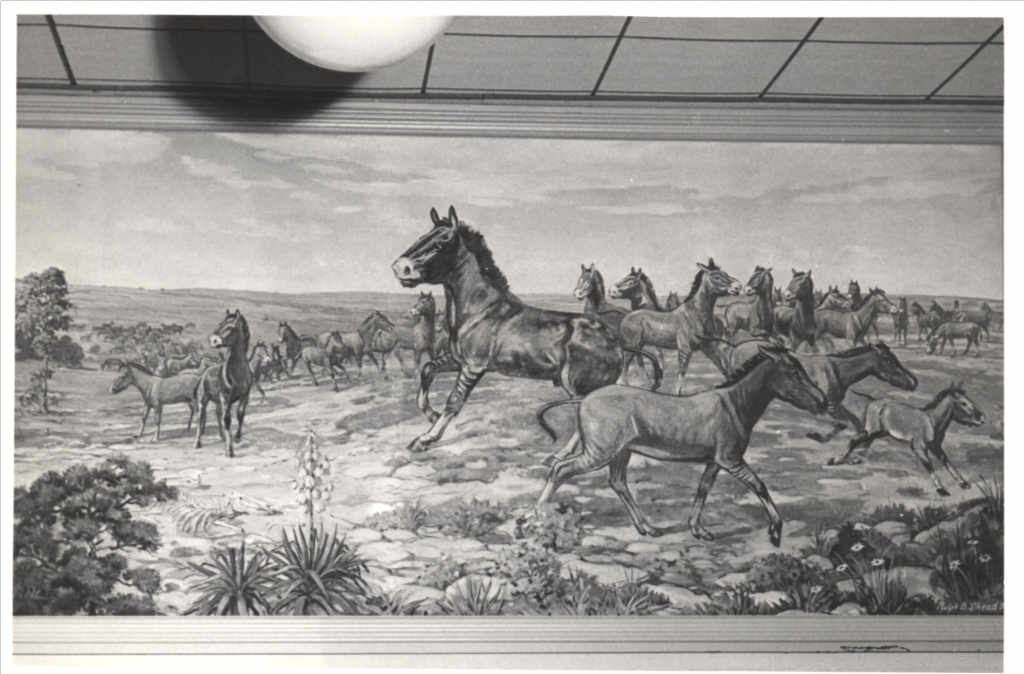

Continuing with the Scooby Doo theme here I get to update one of the most exciting stories that has happened since my time here. You remember my last lament of the missing murals? Well guess what isn’t “missing” anymore!

Continuing with the Scooby Doo theme here I get to update one of the most exciting stories that has happened since my time here. You remember my last lament of the missing murals? Well guess what isn’t “missing” anymore!

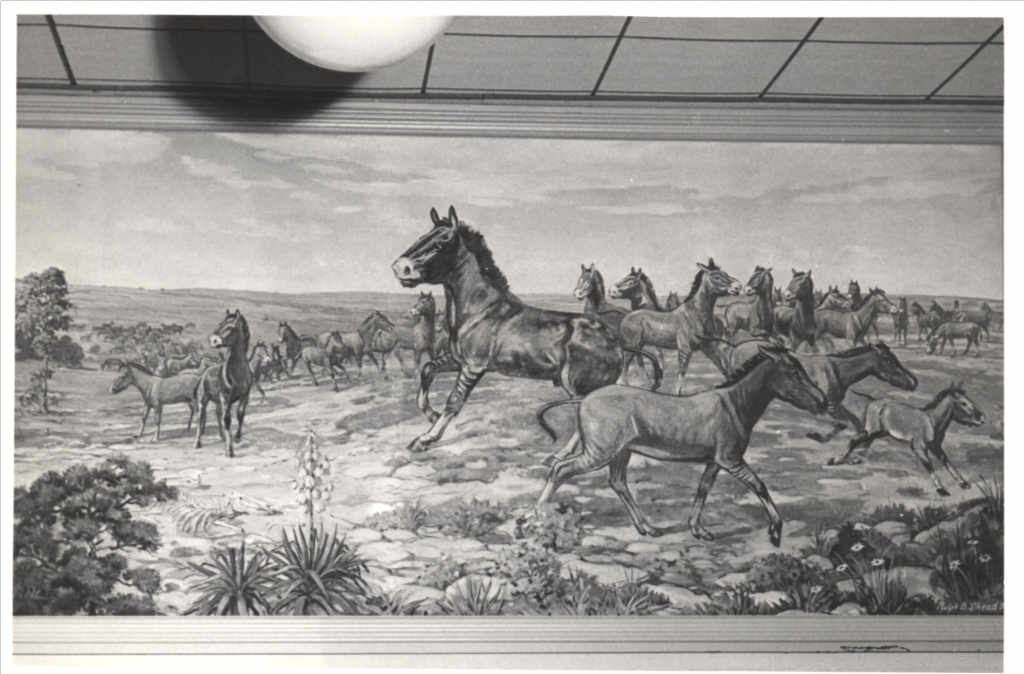

This all started with a mammoth butt.

Some time back (2 years!) I began a project at our natural history museum to scan, digitize, archive, collect all of the images and negatives that were in our Vertebrate Paleontology collection. Thousands of images later a couple things really stand out: The importance of the WPA in the growth of out collections (see WPAleontology) and a couple of large paintings had disappeared since the late 30s and early 40s.

Continue reading Scooby Doo & the Missing Paleontology Murals

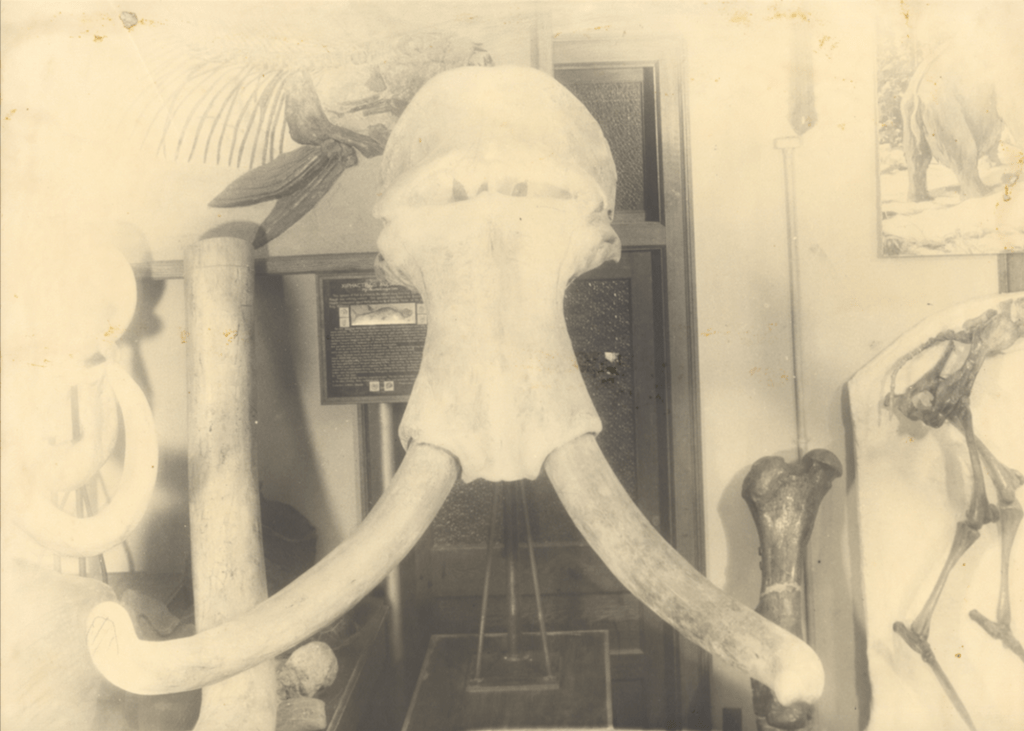

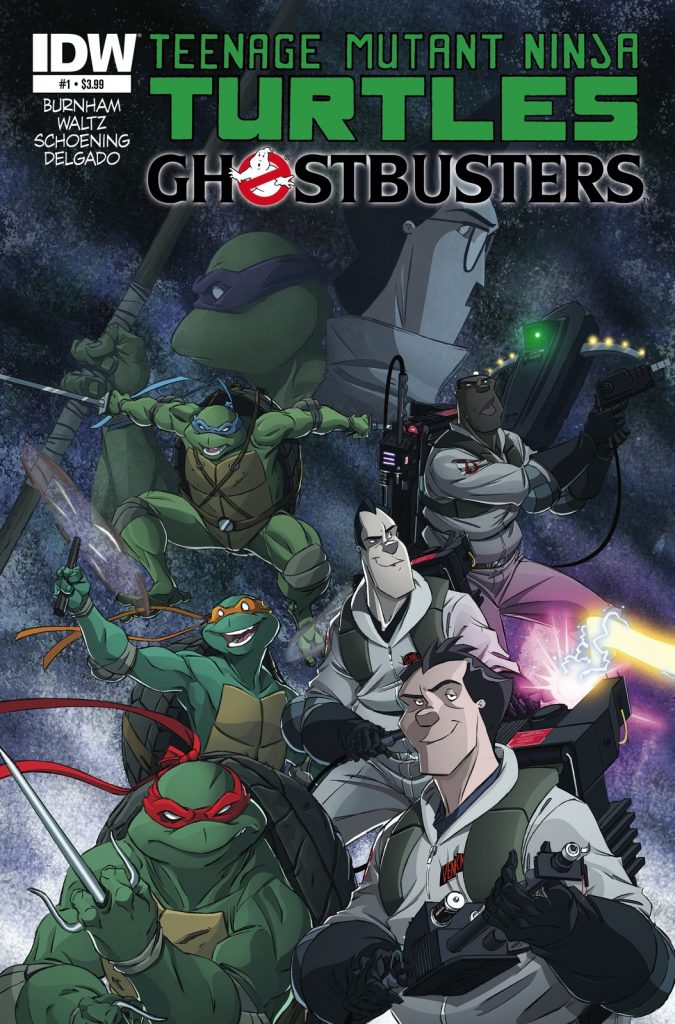

I am not entirely certain, but I think a great part of it might have to do with what I associated “science” and “engineering” with when I was a kid. Even when I was little the idea of scientists in white coats was a bit weird. I had seen them made fun of in cartoons enough to appreciate a caricature. My grandfather worked in a hospital lab and for me such lab coats were for doctors. I never could put my finger on it until recently but as I have went back through the franchises I enjoyed as a kid, I finally realized who I wanted to be:

I know that they are basically the same person, barring the mutation thing. But that was it. Referencing in books, figuring out solutions and answers, the person that people went to for obscure things, that is who I have always wanted to be. In fact, it turns out that when I was 8 I tried to teach myself Assyrian and Sumerian because Egon knew them.

Now, here is the problem: There isn’t a path of study that can lead to that outcome. That outcome is not quantifiable nor does it really bring prestige or money to your alma maters and paters. As I continue to work towards finishing what has become a huge portion of my life I take solace in the fact that all of the extemporaneous stuff I have done through these years have led me more towards being the person I really wanted to be. Whether or not a Ghostbuster and a Ninja Turtle were the reasons I decided to get a PhD, they remain the noblest aspect of this entire experience.

I have learned more about myself in the things I have done to stay sane during graduate school than I have about any topic I have studied. When it came time to pick a major for university I settled on Mechanical Engineering because I was good at math and mechanics. If you’ve taken courses in engineering you can see where this is going. I completed all my core courses my first year in college and realized that I didn’t want to be a career engineer in the sense that we were learning it. I wanted to design and build things, not manage button pushing operations. There is a perfect example of this in Egon’s life in an episode of The Real Ghostbusters: “Cry Uncle”

Real GB #19 Cry Uncle by clist007

In “Cry Uncle” Egon’s uncle shows up and reminds Egon that he said he would come work for him at Spengler Laboratories. There Egon would get to do “real” science. Once at Spengler Labs, Egon has his white coat, and is tasked with feeding the research rats and mice. When he admitted it wasn’t what he expected, Uncle Cyrus explained there are no small jobs in research.

There isn’t inherently a problem with going into a field you are good at, especially if you are interested in it, but for me it was extremely limiting in the scope of my expectations for college. Such expectations continue to shape my opinions of higher education. I think the first thing I found odd was that the way our classes parsed out on the rubric I would be a senior taking freshman speech. Nothing built on anything else. Even the Engineering courses, which were only offered every other semester or so, wanted info in and were built on the premises that you passed or dropped out.

When I went back 5 years later I tried my hand at a broader field: Anthropology. I took every course my university offered and enjoyed them all. I did field work in Belize with another University and ran the gamut of geology towards that degree. Issues of being color blind and terrible mineralogy courses dropped me out of that certification (although I still practive the paleo and science outreach that I learned there) and ended up with a history degree. That itself is just as problematic because everything is formulaic and most of the people at the top hate everyone and have painted themselves into such tight “intellectual” corners that they wouldn’t dare step out of their offices to help someone even if they could.

I even completed an advanced degree in History. Then moved on to combining what I had done and what I thought I wanted to do. History of Science. I worked on another MA, which was worse than History because of the way our coursework is arranged. I still wanted to know more. Not more of one thing, but more in general. There were loose ends that needed to be tied up. So I reached out and ended up taking graduate level hours in Art History and Biology. As I have worked through all the stories I want to tell, and then figuring out how to appease the Academy and still get to write for the audience I want to engage with, I realized that I still want to know it all, and I want to be able to use that to help people answer questions and solve problems.

I still want a lab and a workshop. I doubt I will ever build a nuclear accelerator or a portal device, but with such a practical environment, who knows. I think that this is one of the reasons I have gravitated towards museum exhibits. Aside from presentation and engaging the public with collections (and collecting) there is the technical aspect of getting the displays built, arranged, and installed. Practical needs that people ask you do do.

I still want a lab and a workshop. I doubt I will ever build a nuclear accelerator or a portal device, but with such a practical environment, who knows. I think that this is one of the reasons I have gravitated towards museum exhibits. Aside from presentation and engaging the public with collections (and collecting) there is the technical aspect of getting the displays built, arranged, and installed. Practical needs that people ask you do do.

I think the best thing about all of this is that it took years of advancing schooling to get back into comic books only to find what I study and write about was there all the time. That isn’t to say I write about mutations or ghosts, but a huge swath of my work is science and popular culture, and how the public engages with science. As for my dissertation, it will compare early American Naval and Army expeditions in their scope and treatment of the scientists (naturalists) and artists as were full expedition members. The first one, The United States Exploring Expedition (U.S. Ex.Ex), was in many ways undertaken due to John Symmes’ insistence and marketing that the Earth was hollow.

Even my PhD advisor admitted that my niche might be in being a generalist.

As of 12:30 Thursday, March 30 I am officially “ABD” which as I said when I tweeted that out, stands for “Should be writing.” Actually it stands for All but dissertation, all but done, or all but dead, depending on who you talk to. Logistically this means I have 15 hours of coursework left before completing the degree program That means I have 15 credit hours left to write my dissertation, defend it, and graduate. The last thing due before that whirlwind of excitement though is my dissertation prospectus, which, as every other part of this experience has been, is completely different for everyone. I have some friends that have turned them in as paragraph abstracts because their advisor’s believe it is just for the student to prove they are thinking about the project. At OU the prospectus meeting is due within 3 months of your defense.

But that is getting ahead and this post is really about looking back. If you have been following up to this point you will know that nothing about how I prepared for me exams followed any sense of traditional work. I do no possess a single notecard with any information written upon it. This isn’t because I burned them all in celebration, it is because I never took any. I have never liked notecards at all, and a stack of loosely connected bullet points wasn’t going to get me anywhere. What I do have though is thousands of words here written as a progressed through my reading lists making connections, shifting my ideas, and sometimes changing my understanding of works based on new sources.

What I also possess is a renewed hatred for the formulaic framework of academic writing. It is terrible and it never leads to a true understanding of the arguments presented. It only exists to make it easier for other academics to guy and skim your book for your points, to search your citations and see if they agree with them or not, it is never about you or really your work. The Academic tradition is a snake devouring its own tail as the world around it has blasted into the 21st century it is wallowing in its own memory institutional filth. Every single problem with the system of publish or perish could end in a single generation but no one really wants to because that would mean the whole game they have spent years and money learning wouldn’t work the same way. The journal publishing houses are worse than the books (excepting textbook publishers). The continued maintenance and control of such non-entity hands would never be tolerated in any other University matter, but this one serves to reinforce the specialness of those publishing.

Following that arc, something that I found of great interest were the reviews for many of the books on my list. The first 1/3 of the sources (Natural History and the History thereof) was heavily reviewed, many with multiple, sometimes disagreeing, reviews showing up in a swath of journals. The second portion of works (American Studies) were less reviewed both in number and diversity of journals, possibly due to American Studies existing as this ephemeral discipline in many Universities. The third, and for my work one of the more important aspects of my exams (Art and Art History), was almost non-existent. Trying to place these works and artists in a historical context is an uphill battle when all you can find are a few gallery books, an encyclopedia entry, and maybe an “about the artist” blurb in permanent collection. More often than not the “reviews” I could find were from librarians whose sole purpose it was to recommend books for pubic libraries.

With those unpleasantries out of the way, I will walk you through the three days of testing and (skipping the three weeks wait) the oral defense. Our testing procedures here only recently changed. Before you would had to slog to campus by 8, get your questions, and sit in a tiny room with a computer with no internet access and type out your answers. (After all you have to prove what you know and like the language exams here, you would never ever access a computer or the internet during your research). Now, thankfully, the process is a little less draconian. You can take your exams wherever you wish, utilizing your notes, books, and computer (you know, as if you were actually a working scholar). You have your questions emailed to you first thing in the morning with your instructions on when they are due back. Then you write everything you know.

Mine were done on a Tuesday, Thursday, Tuesday rotation. Armed with a printed and bound collection of the book reviews I could find and the blog posts from here (I used blogbooker.com to export and print these notes) I waited for the first email. All three days worked pretty much the same way, I got up, did my regular morning routine or treadmilling and breakfasting before heading into our spare bedroom/office for my mission should I choose to accept it.

I queued up the entire season of Scooby Doo, threw on my headphones and started answering questions about the nature of 19th century nature and those who decided that what was. You can find the questions and unedited answers on the PDF page of this site if you want to spend some time with that. I started at 8 or 9 depending on the day, which meant they were due at 4 or 5 respectively. The way that I constructed the day was one part of the question, stop for lunch, tweeting my progress, and second question. This may not work for everyone and I talked to people that were too nervous to worry about food for the day, I don’t recommend that, but some people don’t have control on their anxiety levels.

My answers were around 6000 words in two parts, and I finished well before the allotted time expired. There are some spelling and grammar mistakes throughout (kind of like these posts), but I have always had this terrible habit of changing things when I edit, even when copyediting which defeats the entire purpose of editing. I have come to terms with needing a good external editor for things so they will be finished and correct before going to press.

–Three Weeks Laters–

I have a dream team of a committee and they are almost impossible to track down at the same time. This is one of the reasons the oral defense was so far away from that last “send” push. I like my committee and I have worked closely with everyone on it. I enjoyed my reading list for the most part too. I was looking forward to my defense, not because I was expecting to be grilled, but because the very people I learned the approaches to my work were going to be there to talk to each other as well as grill me. I was asked specifics on some of the more broad examples I used in my answers, I was asked about framing answers in a certain way or starting at a certain position (specifically the West as America for the beginning or the changes in scholarship answer). My answers were satisfactory, and I was indeed pushed to the point of having to say “I don’t know” which I have been told on several occasions is the main purpose of this medieval academic hazing process. Congratulations were given, signatures were collected, and the official paperwork was taken to the Graduate College.

And that is it. Pretty anticlimactic for as much time, energy, equity that was put into the preparations, right? The preparation is the key, the exams are just a formality to give the preparations an endpoint so you don’t continue reading one more thing for the rest of your life. For me, the next step is hammering out a prospectus. Mine will definitely *not* be a paragraph abstract. One thing that I hope to implement will be a digital component to the work. Originally I wanted to rework a website (not this one) for the U.S. Exploring Expeditions and the Pacific Railroad Survey Reports so they could be explored, remixed, etc. Now, I believe I have a better option that might actually be able to happen. My hope is to get good high resolution scans of all these journals and taking all of the plated out to create a huge digital atlas of the prints. The images could also be shuffled and arranged via meta data by content, location, type, etc. I will update that part of the project here as well. Until then it is back to the irregularly scheduled programming, and I have a couple ideas in the pipeline. As I start work on my dissertation, I will try to keep Sunday’s free for afternoon updates on that process and any other musings that come up along the way. This whole process was incredibly useful for me, and I don’t think I could have been as prepared for my exams had I not thought through the contents here and besides there is nothing quite like failing in full view of the public. Not only was it useful because writing is a way of thinking, but sitting down every week or so and hammering out an average 2000 word post was a great exercise in extemporaneous writing. If this whole process helps just one other person, it was more than worth it for me. I have gotten my use out of it, but maybe a first generation PhD student perspective on this whole thing will help someone else too.

~If you are interested to know, to answer all three questions I watched through all of the original Scooby Doo, Where Are You? season 1, and The Scooby Doo Show 1 and 3 (2 is short and bizarre) and got about halfway into Season 1 of What’s New Scooby Doo.

This one really isn’t about comps, but I wanted to use it as a wrap up to that project as well as 2016. Besides, it is best to have something of this magnitude end on a nice round number like 20, isn’t it? I mean, base ten are some of the most celebrated milestones.

As 2016 comes to a close there will be tons of lists and predications, dedications and memorials. Seems like there might be more memorials this year than some in the past, but I haven’t taken the time to compare death notes. For me, it was spent in full preparation to take general exams (or comprehensive exams depending on what your people call them) as the last hurdle before dissertation. Technically is is next to last since I have to present a prospectus for my dissertation within three months of completed my exam defense. The questions will come in the Spring. I meet in a couple weeks to schedule them. The written will occur on three different days and the oral will wrap it up. When the questions arrive I will choose two of the three that are offered and I have 8 hours to answer them. So the all of the previous posts for comps prep will be distilled into 6 four hour extemporaneous writing exercises roughly corresponding with the larger divisions in the reading list.

Those posts can speak for themselves at this point, what has been really interesting for me as I take stock of the previous 12 months has been the non academic stuff that has kept me sane from all the academic synthesizing, to wit: I watched cartoons and painted. On the cartoon front I watched through the entire run of the Real Ghostbusters AND the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. I am currently working through the 2003 version of TMNT while puttering around on the treadmill in the mornings. The most interesting aspects of this were the final seasons that had moved to cable that I had actually never seen. I am sure there will be ruminations on that later, or whenever.

But for my wrap up of 2016, here is the art I created (not counting the matting and framing I did). The pastels are copies of some Ghostbuster trading/art cards that were released by cryptozoic, they translate perfectly to pastels.

I didn’t make any predictions going into 16, and I don’t think that I will hazard any going into 2017. But I do hope that I manage to do as much of this ridiculous cartoon art as I did this past year. More than one person commented that I was the Bob Ross of Ninja Turtles, so there may come a time when I go a step farther than a simple time-lapse and walk everyone through a piece featuring happy little mutants. Happy New Year All!

This will be my shortest post: I’m done.

The End.

To wrap this list up there are several books which were recalled that I read several weeks ago and am working from my notes on for this. That being said, there wasn’t anything new in any of these books that wasn’t in some of the earlier reads/posts. That doesn’t mean they aren’t interesting or useful, they just add more content to the footnotes when you defer you opinions to someone else work. I will look specifically at a few of them, but will include the rest in the list/images just for completion’s sake.

It would probably be best to track through the ones least used here, but likely to make an appearance in my dissertation, or at very least my prospectus which I will get to working on soon. Edward Wallace’s The Great Reconnaissance: Soldiers, Artists, and Scientists on the Frontier 1848-1861 looks at a sliver of time when there was much traveling and reporting back from the American West. Interestingly enough this sliver doesn’t cover much in the way of the miles covered before 48 and after 61. It is a great book, but like many on the same topics, it needs updated and contextualized. It does provide an excellent paper trail for journals and reports to follow.

Ann Shelby Blum’s Picturing Nature: America Nineteenth-Century Zoological Illustration is a gorgeous book. Filled with color images from some of the most important works in Natural History. Blum focuses on scientific representation outside of the main thoroughfare of historical enquiry and anyone wanting to know more about people who aren’t Audubon. She also puts Audubon in a natural history (and thus science) perspective. Considering the history of natural history as the history of science should not be that revolutionary, but here we are.

The collected Art and Science in America: Issues of Representation, edited by Ann Meyers, is a collection of papers from a Symposium that was focused on the Huntington’s collection and how two-dimensional images can provide primary source material for understanding the early decades of the 19th century. The book was published in 1998 and was reviewed as part of the “rebirth” of studies in historical natural history.

Wendy Bellion’s Citizen Spectator: Art, Illustration and Visual Perception in Early America is a great collection of early American art styles and art cultures. It would be an excellent book if it was more readable. It reads like a dissertation (and it very well could be) but it will likely fall flat on more readers than those who appreciate it. The book distills down to the fact that spectators (active lookers–“participants” in art) were making decisions about and utilizing their own positions within the republican value system that was the early American experience. Participating in these exhibits, art illusions and allusions were what shaped the citizenry, hence “Citizen Spectator.”

Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America by Susan Shulten is a fascinating exploration into the history of cartography not from the technological side as much from the cultural side of how thinking with and about maps has changed. The changed was sculpted and molded through active history making. This is perhaps one of the best representations of how scientific visualization has changed and the power that such imagery possesses. Tying this back into Bellion’s theories on spectatorship as a means of reinforcing citizenry and you can start to see just how powerful images can be. Maps may fall under a different context than the wildlife imagery in Blum’s Picturing Nature but they are all politicized in their own ways and are important to consider as products of scholarship and not merely visual aids. Incidentally, you can look at all of Schulten’s maps (and visual aids) at MappingtheNation.com

That idea of visual aid as science comes into play well in Barbara Novak’s Nature and Culture: American Landscape Painting, 1825-1875. The idea of scientific representation within government reports might not seem revolutionary at first thought, but where Novak succeeds is providing the general context for the artists–specifically landscape artists– on the government expeditions. There is much more to this book, and it should be paired with Rebecca Bedell’s The Anatomy of Nature: Geology and American Landscape Painting , 1825-1875 for best results (including forgetting which one you read what in).

The landscape was the “New” World’s answer to the Old World’s man made monuments. As technological advances brought photography into the government reports artists were still needed to provide the colors to go with the matching black and white photographs. Both in this sense were visualizations to accompany official reports. They were science, not art. Just like the charts or graphs, photographs and landscapes were supposed to present hard facts and data. Artists even complained that realism was science and not art.

Kenneth Haltman’s Looking Close and Seeing Far: Samuel Seymour, Titian Ramsey Peale, and the Art of the Long Expedition follows the first American expedition with “trained civilians” that is artist on payroll. Lewis and Clark suffered from the lack of artists and the government was not going to repeat that mistake. Titian had watched his father sketch many of the Lewis and Clark specimens as they were deposited in Peale’s museum. While Seymour’s works are rare and Peale’s Long Expedition art is scattered to the four winds Haltman works to provide an account of the first American “artistic” enterprise. This also serves as a good introduction to my own work, with Lewis and Clark and Long setting the stage for the U.S. Exploring Expedition, on which Titian was artist and naturalist, just as with the long expedition, but was a naval expedition. Titian provides the best way to understand the differences in naval and army expeditions in the antebellum period. The one thing that Art historians like Haltman and Flores haven’t touched on, but provided an excellent template to work with is that natural history representations are science. Looking at this expeditions and representations as the history of American science in broad terms (more specifically geology and natural history) is sorely lacking from any of the books I have read on this mammoth list. The idea that Titian’s first sketch of the scissor-tail flycatcher is important for art is only half the story. The collections, sketches, and preserved specimens are history of science. You would think this would be low hanging fruit. Then again, maybe it means that my work will not be in vain, lost, or ignored. We will see. I will have to post my wrap up thoughts for this project and the whole year in a few days, exams will be scheduled in the spring and I have some ideas on formulaic academic writing, writing for the academy, and the cost of such works that I will post after I pass exams. Thank you for coming along on this mad road trip and I hope that if you are preparing for your own exams you find some of this madness comforting towards your own work, if you are here for morbid curiosity I hope it was satiated.

It’s Christmas Eve, so what better time to post my Road to Comps Eve post. One more set of readings and I will have completed the entire list AND 2016. I hope to make my final post next week too.

These last couple of sections are bits and pieces of larger works and many of the points have been made in previous posts (and previous books) but they serve as having another place to return to pull information in order to make the points in my dissertation (this isn’t entirely for tangential exams to prove I can stay on a task for an extended period of time).

William Truettner’s (editor) The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920 was something I had seen in class before. It serves as a textbook for image use in promoting the west to settlers and to modern museum visitors. Interestingly enough the book was published in 1991 to accompany the contentious art exhibit.

The following year William Cronon edited a volume entitled Under an Open Sky: Rethinking America’s Western Past (see a trend here?). Martha Sandweiss’s contribution predated her book Print the Legend by a decade, but many of the points she made about photoraphy are relevant to art as well, as I argued in the previous post. In short, art should be considered as primary source material within its cultural context and it should not be taken at face value.

Robert Cushing Aiken’s “Painting of Manifest Destiny: Mapping the Nation” appeared in American Art Vol 14 (Autumn, 2000 pp 78-89). and collects several of the key art pieces used to represent the American tenet of full continental settlement.

Claire Perry’s essay “Cornucopia of the World,” (Pacific Arcadia: Images of California, 1600-1915) highlights the trouble western promoters faced when the gold ran out of them thar’ hills. The focus shifted from mineral to agricultural wealth. This was not an easy 1:1 substitution as the arid areas of California couldn’t be farmed in any way remotely resembling farming practices in the east (or even the midwest). Interestingly enough, this preambles the turn of the century tourist boosterism that came as Americans became more autonomously mobile.

Barbara Novak’s American Painting of the Nineteenth Century: Realism, Idealism, and the American Experience is in it’s third edition (1980, 1995, 2007) which shows that understanding American art in its own context isn’t a simple project. The strength of Novak’s work is intensified when you can look at it in tandem with the David Reynolds work on 19th century American Cultural History. Novak provides the in depth artistic analysis and Reynolds provides the larger background to help frame it.

Stephan Oetterman published an enormous treatise on the art of the panorama. The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium is a fascinating look at a (literally) huge pieces of American art. To understanding the draw and experience of the moving panorama you can see this previous post. Oetterman’s research indicates that far from the generally accepted idea the the panorama was based on ancient ideas (or ideals) is erroneous and it was in fact patented in the late 18th century. Part of the draw for this type of artwork, stage or no, was increased with the western landscapes and light plays that were highlighted in the few other gallery books included on this list. he even points out that movies in the mid 20th century were produced in cinescope which mean that it took three projectors and three screens to capture it grandeur of the west.

Beautiful books that provide extensive examples of their respected topics are

Linda S. Ferber The Hudson River School: Nature and the American West

John Wilmerding (ed) American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850-1875.

Andrew Wilton, American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States 1820-1880

This final piece repeated a lot of what I have already written about the expeditions west, but there was something extremely interesting in how this book had been used.

John Rennie Shorts’ “Mapping the National Territory” chapter in Representing the Republic: Mapping the United States 1600-1900 was heavily annotated by someone who used it before I did, but only in some interesting places. Actually what was most interesting was where there weren’t any annotations.

As long as the book was recapitulating the same stories on the expansion and expeditions by the government the previous patron filled the pages with notes. Once the book started talking about the geological surveys: nothing. Well, almost nothing, there were two sets of brackets. Even as the book stated that little attention was paid to scientific surveys–even though they made up 80% of all the surveys were scientific in nature (mostly geological).

All this leads me to believe that my dissertation topic is not only interesting but might actually end up being useful to a couple of fields. One more section and a few more books and I have completed this part of the journey, the next post will likely be short like this one since the remaining texts are larger works as well with only portions aimed at my topic and it is hard to review/synthesize a textbook outside of its content’s context which has most definitely been carried on in previous posts. I think these last dozen books or so are just the mopping up portions in order to hammer home some of the larger points and make sure I have been paying attention all this time. If any of this stuff was new and revolutionary at this stage I would most likely be extremely worried about my progress and exams.

I have found it odd that the case has to be made to study photography and art as source material and not merely “visual aids.” The only think that is even more odd is that this case is relatively recent.

The four books and one article in this little operating section tend to all say the same thing–photographs are important not because they are photographs, and not even because the subjects of the photographs, but because they represent a distinct moment in time of an ever-changing culture. The contextual culture of regional and temporal data are frozen in time just as the faces of early portraits. Each work provides its own examples of why this is an important shift in thinking about images. As Martha Sandweiss points out in Print the Legend sometimes what isn’t photographed or what was photographed and then lost can reveal as much (if not more) about a certain moment in the past. Sandweiss provides a solid foundation that scholars should use in reassessing their relationships with photographs. I believe this improved methodology will also easily cover other visual culture as well. Print the Legend could easily be a history of technology work as it follows the exponential developments of photography across two generations (her investigation ends in the 1890s) which happens to parallel the development of America’s mythos regarding their newly acquired and explored territories. For my purposes, she provides the best answer for why, after a MA in American History I have shifted over to work with the Art Historians for my dissertation:

“A lingering bias in historical training teaches would-be historians to value the literary over the visual or material, and teaches them how to query, challenge, and interpret literary documents, while leaving them few analytical skills for the interpretation of visual records”

While looking back through some of the little work I have done with photography (only really starting in 2014) I did find a C-SPAN video of this very book, and it is worth the time you can devote to it:

A funny aside is that you can purchase this as a DVD or an MP3. The latter of which you can listen to Sandweiss describe the photographs, which leads one to believe they missed the point.

Alan Trachtenberg’s Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evens is one of the earliest books (1990) to call for a shift in the understanding of photographs. It is one of those books that requires complete attention and an appropriate amount of pyschological working up to undertake. It is dense.

Not in a bad way, but at times the theoretical asides (which I am certain Trachtenberg does not see as asides) get in the way of the point he wishes to drive home. My first run in with Trachtenberg was his first book about the Brooklyn Bridge. While reading this I went back and thumbed through some things in it on a hunch. Photographs does continue Trachtenberg’s thread of America as imagination. In fact in 1965 he called it “An America of the imagination.” In addition to starting the stone rolling on photography reassessment in history, Trachtenberg offers a short sentence that I am certain will come up for expansion in my future work:

“Thus O’Sullivan placed the survey camera among the instruments of practical science, allowing the history and meaning of the Western surveys (the conjunction of “pure” science and imperial economic enterprise) to reveal their contradictions” (289)

The remaining books in this section could be considered “popular” books each focusing on a single photographer as they managed to work their way through the new continental nation and new technologies in order to make names for themselves as photographers.

In Meaningful Places: Landscape Photographers in the Nineteenth Century American West, Rachel McLean Sailer highlights that print making and mythmaking went hand in hand. Few of the landscapes are void of human life or activity, to the contrary many settlers used photographs of themselves in their new spaces as vindication for the success and progress of American culture. Photographs provided constant reassurance that people were indeed where they belonged. A sense of place for people who had left their cities or even countries in the case of foreign born immigrants was something that most settlers struggled to maintain, but photography, according to Sailer was instrumental in calming some of those unspoken fears.

Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis is another notch on Timothy Egan’s literary gun. I have personally read two other of his works: The Worst Hard Time and The Big Burn. Egan doesn’t write books you can glean which is one of the reasons I enjoy assigning them. The book itself follows the drama of Curtis’ life as he moved across the West capturing moments that were fading away. The story of forgotten photographs rediscovered are as much the legend as Curtis’ “quixotic” quest to capture native life. Which I think is captured better in this variant cover:

The renaissance of his work in the 1970s installed Curtis at the forefront of historical photography. Even as historians in the 80s attacked his work for being staged or “playing dress up.” Egan points out that Curtis heard these attacks during his life, and never denied it. His defense provides insight into his work and the importance of photography in the late 19th century: he wanted to represent the past, not document the present of the future. His time in Oklahoma in the 1920s saw many of the natives already fully remodeled into Euro-American culture and his pace in his “race against time” hastened. For Curtis himself, the 2001 documentary Coming to Light is an excellent way to start. I apologize for the ads in the linked video but it was the only site that had the full program to share. Here is a snippet. You can see the whole thing here.

Curtis was involved in the Harriman Expedition in 1899 which, at this planning stage, will be the final expedition in my dissertation. Curtis also employed the new technology of moving pictures after the turn of the century, which ties back into the final book of Eadward Muybridge.

As with Sandweiss and others, the nature of photography in the American West also serves as a history of technology. Nowhere in these readings (maybe even more broadly) is that more evident than in Rebecca Solnit’s River of Shadows: Eadward Muybridge and teh the Technological Wild West. In fact, Muybridge’s life can be seen as a parallel with both the arc of the West and the rise of photography. He “invented” himself in western culture, photographed through the landscapes as did his contemporaries, and then made studies with the movement displayed in still photographs. His moving pictures were the legacy his family life never produced. Solnit describes Muybridge as a man who “split the second,” which had “as dramatic and far reaching [effect] as splitting the atom” (7). One reviewer did not care for this phrasing, but given the circumstances and the tenor of the book (and Muybridge’s life) I think it fits.

The final piece was an article in the Art Bulletin in December 2003 highlighting Timothy O’Sullivan as a survey photographer. Trachtenberg mentioned O’Sullivan in the quote above as the person who brought photography into the came of scientific instruments. Robin E. Kelsey’s article “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74” look at the photographs as a new form of graphic representation. That is a more precise way of expressing the landscapes, forms, materials, etc that the survey encountered. “Pictorial Rhetoric” became the tool for people like Ferdinand Hayden in order to increase (or sustain) federal appropriations for their continued surveys. One of the mor interesting portions of the articles many photographs is the sort of “line of custody” we see in O’Sullivan’s (i.e. The Survey’s) photographs:

A final thought on this reframing of photography as primary sources is stirred by the author byline in Kelsey’s article. “He is preparing a book on Survey photography.” If the article is any indication it will be an excellent book. I wonder though, if the pendulum is swinging too far into the study of photographs as primary sources that they will become more detached from their created context as they become topics or study. Something like Survey photographs is an excellent topic to undertake, but at the time the photographs, as graphic representations, were another means of transferring information and raising interest in the surveys, government exploration, and the American West as construed by the myth-makers. I think it shows the power of photographs to evoke audience interest and emotion that no popular book has been written on the Survey graph or map making or their field reports as entities. Journals have been reprinted and photos as well, but I think it will a long time before the similarities and differences between visual and literary will ever be hammered out.

This will be one of the shortest posts made on this travelogue through everything in print (Every time I start this way I drone on for over 1000 words). This is not due to the end of the semester doldrums (I’ve been on 12 -month work contracts since moving up here) or the holidays (I’d rather not do them), but because the bulk of what I have read is review of review of things that I have already written about at great length. In fact, it was precisely such foci that started my posting in earnest as I collected and transcribed my notes for class. In addition to typing up the notes I was able to track down most of the images that we used in class and included them in with their appropriate author. There is no need to re-invent the wheel at this point, so I will link to them throughout the post. This is an excellent time to realize that my previous work is now back paying dividends.

Before moving on to the two main points I want to make in this post, I wish to take a moment to remark on the shifts of formulas in the books read about individual artists. I have moved on from the rubrics of “academic” writing and fallen into the interesting (and more visually appealing) gallery books that accompanied exhibits across the United States (and sometimes farther). These collections of essays group around the artists whose work is on display and offers just enough insight to be interesting but not so much as to be overly useful for comprehensive exams preparation. I have enjoyed them though.

Early in my foray into the Art History department I made a remark about there being so few artist biographies. One of the other students (now a director at a museum in New Mexico) voiced disagreement, but offered no examples outside of these collected essays or a few pages of encyclopedia entries. I still stand by my complaint. I am not suggesting separating the artist from their work, but more bringing in as full a context as we can manage for the world their work was a part of.

What can be done is something along the lines of what Benita Eisler does for George Catlin in The Red Man’s Bones. I have read this book once before (and never got around to reviewing it which was what this whole stupid spelunk into blogging was supposed to be), but reading it a second time after reading about the culture of the growing United States, showmanship, art, and European tours, it is an even better example of taking someone who is currently existing “out of time” and putting them back into the structure that shaped there careers. For my take on Catlin see this old post.

Bierstadt and Bingham both have (excellent) posts of their own as well. I was actually able to visit the Bingham exhibit Navigating the West (which is the exhibit book that I just finished) and get a tour with the co-curator Nenette Luarca-Shoaf.

One of the best books in this section that isn’t currently being held for ransom by some other library patron (the Winslow Homer book will have to be edited back in this post or added to another one when it finally gets returned to the library) is Robert Taft’s Artists and Illustrators of the Old West 1850-1900. Each chapter is an excellent overview of an artist or a set of artists working in the same genre or region. Each one of these chapters could easily be made into a book. In fact, taking Taft as a starting point and Eisler as an end template I think one could make a lasting furrow into that lack of useful biography thing I mentioned earlier. The kicker with Taft’s work is that is was published in 1953. On a hunch I emailed one of my professors and asked if there were any updated versions or had anyone added to it. He replied there were some updated materials but no one has done it better than Taft. After finishing the book, I have to agree. It is one of those that has been added to the “purchase own copy” list that is an outgrowth of this project.

One of those included in Taft’s survey was William Jacob Hays. I bring this one up here because he might be lesser known than anyone mentioned here (or even in Taft’s book) but produced one of my favorite paintings that I have actually seen because it is at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa: Herd of Buffaloes on the Bed of the River Missouri. The sheer mass of the megafauna portrayed in the river bed give an idea of how many buffalo there were. I suppose thinking back to the environmental histories I have read here, it really is sort of the same thing as Burroughs’ poetry about nature and descriptions of the Passenger Pigeons. (this whole endeavor is turning into Dirk Gently’s Holistic detective agency).

Moving on from Taft and Buffalo I want to end with Alfred Jacob Miller and horses. Like the others I have reviewed Miller in previous posts but there are a few points to add here, less because they are new to the discussion and more because they are familiar to my life before the university: horses.

At the height of or equine days my family had 17 horses full under AQHA values, papers and all. Our number one stallion was born two weeks before I was and only recently died a year ago. Turns out he was 96 or 98% Foundation Quarter Horse which means that I could have completed all of my schooling and advanced degrees with the stud fees we never charged.

I tell that story to set up the one about Miller’s horses. When we first started looking at Miller’s paintings in class I recognized his horses all looked like Arabians which where the stock the Spanish brought back to the United States (I saw “back” because paleontologically speaking horses first evolved in the “new” world before invading the old and going extinct here). I never thought more about it until reading more about the complaints people have about Miller’s horses. They were too Arabian to be authentic wild ponies that the Indians were riding. This is the keystone in this whole putting the artist back into their context lamentation I keep tearing my sackcloth over. Miller may best be remembered for his commissions for the Scottish nobleman William Drummond Stewart.

Miller only ventured west for a few months of his life. His real mark of success (by that I mean living comfortably off his art) was back in Baltimore where he set up his studio in the center of the trade offices of the merchants, bankers, and lawyers. Just like real estate art patronage is all about location, location, location. These were the wellest-to-do of New England and were part of the growing trend in thoroughbred horse breeding and racing of which Arabians was choice starting stock. These were the people purchasing Miller’s work and commissioning his time. They expected to see Arabain horses, so that is what Miller gave them. Miller clearly had a feel for his genre, but he also had a handle on the desires of his audience. In addition to the real estate location, he also mastered another rule central to all forms of artistry–know your audience.

Just so they are most included, here is the link to my Karl Bodmer and Thomas Moran posts too. I will come back and add anything pertinent on Frederich Church or Winslow Homer if I find anything in this book:

The culmination of that course and all that blogging was a huge paper that was one of my favorites of writing since being at OU and, as it happens, may actually be a full third of my comprehensive exams: Artists on Expedition: Artifacts, Authenticity and Authority in Early 19th Century American Art of the American West.

Art and the American West is the most recent undertaking of my long and checkered career as an academic. Since finishing my MA in the History of Science, Technology and Medicine I have spent a great deal of time in our Art History department learning ways to tie in the arts to the American cultural studies that I seem to have fallen into in recent years.

The greatest benefit to getting into a program at this late in the game is that you are still interested in the topic and it hasn’t been completely scraped from your soul by years of arguing theory. I have always said that the surest way to remove any of the joy in literature is to study it at university. The same can be applied to art.

Since I have been involved in the courses or the last two years, the three intro books on my list are excellent reviews for stuff we’ve talked about in class. In class we spent more time with articles and visual analysis and less with the broader portrayals and involvement of the artists, art (as object), and art (as culture) within their historical context. This is also the same field that led to the more structured development of this blog and eventually the webpage where it lives. Many of the individual artists that will come into play in the future posts will be linked back to my first art history works that used some of the books in the series as part of the courses I was taking.

From what I have been working on, I find it is completely impossible to understand the antebellum period in American history without understanding its art. All of these overview books are collections of essays that isolate major themes and then reapply them back to the larger American Cultural landscape.

Reading American Art (Marianna Doezema and Elizabeth Milroy) offers a handy collection of American Art and their interpretations through the academy and through time. The survey runs from the colonial period through to Jackson Pollock. For my purposes the usefulness of this collection comes from the analysis of the early 19th century establishment of art as American. There is much lamentation over the fact that Americans had little pride in their own form of art. The hardest question to answer or explain is the schizophrenic nature of early art in American that needed to prove it was its own thing while striving to make it work on European terms. Political history sets up the development of this art form less in manner of than artists and more in the manner of the artists’ patrons. Whigs and Democrats in the early to mid 19th century were both striving to arrange the new Republic in a manner that benefitted their constituency. The lack of any actual aristocracy and the expansion os suffrage to those who did not own land drove the Whigs to seek control over American culture where it had lost control over American politics. Instead of calling themselves Dukes or Lords, they opted for the title of patroon and shifted to constructing reflections of American culture through their patronage of early American artists.

American Icons (Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Heinz Ickstadt) is a larger format and, frankly, easier to read version of Reading American Art. The essays are all arranged from a comparison perspective between American and European art. Many of them are comparing the differences in the American arc from those of their European counterparts. Save one. William Hauptman’s essay “Kindred Spirits: Notes on Swiss and American Painting of the Nineteenth Century” looks at the parallels with Swiss and American art, most notably the fact that national artists had to leave the nation (Switzerland or the US) in order to make their names and (however measly of) fortunes in the art world. The most interesting aspect beside the timing is the cultural arrangement of Switzerland that can be used to illuminate that of the American side. With a population less than that of New York of City, Switzerland was self divided into regional cultures that “shared more differences than similarities” and led to a multifaceted emergence of “Swiss” art. (Contrary to popular belief Swiss art is not art that is full of holes).

Finally, Barbara Groseclose’s Nineteenth-Century American Art is part of the Oxford History of Arts series and is filled not only with useful chapters and asides, but with further reading and sections on which museums to visit to see some of the famous collections of American art. As with the others, Groseclose starts American Art in Boston and follows it through the development of art unions as “culture” spreads through New York and Philadelphia. One of the strengths of this book is that was published with most of the art images in color. Even Reading American Art which sold itself on being a collection of essays intended to remove the need for bad photocopies of articles and aides for teaching class was published without colored images.

These intros all serve to orient oneself in the larger field of American Art History as it pertains to the Antebellum period which all have mentioned is a bit of a black hole of art history theory (which I think is one of its strong suit) even as it proves to be more important for the development of the culture of the young Republic than it at first seems. You can’t separate early American history from early American Art History and have either make any sense. Many of the artists that have works in this books were mentioned by name and covered in the books of the previous posts. Even those like John Haberle, and William Harnett who aren’t as famous as Bingham, Bodmer, or Bierstadt (who ironically, may not be that popular either given the number of times these authors talk about the obscurity of American artists in the 19th century. These early collections and studies from the mid-late 1980s all remark that this period in Art History has fallen under that research of American Cultural History and American Studies departments which means I have been on the right track trying to put it all together to understand a more complete America during the long 19th century.

I will end this with the same thing I tweeted when I finished the last book: “It should be illegal to publish black and white images of colored art works in art books.”