As of 12:30 Thursday, March 30 I am officially “ABD” which as I said when I tweeted that out, stands for “Should be writing.” Actually it stands for All but dissertation, all but done, or all but dead, depending on who you talk to. Logistically this means I have 15 hours of coursework left before completing the degree program That means I have 15 credit hours left to write my dissertation, defend it, and graduate. The last thing due before that whirlwind of excitement though is my dissertation prospectus, which, as every other part of this experience has been, is completely different for everyone. I have some friends that have turned them in as paragraph abstracts because their advisor’s believe it is just for the student to prove they are thinking about the project. At OU the prospectus meeting is due within 3 months of your defense.

But that is getting ahead and this post is really about looking back. If you have been following up to this point you will know that nothing about how I prepared for me exams followed any sense of traditional work. I do no possess a single notecard with any information written upon it. This isn’t because I burned them all in celebration, it is because I never took any. I have never liked notecards at all, and a stack of loosely connected bullet points wasn’t going to get me anywhere. What I do have though is thousands of words here written as a progressed through my reading lists making connections, shifting my ideas, and sometimes changing my understanding of works based on new sources.

What I also possess is a renewed hatred for the formulaic framework of academic writing. It is terrible and it never leads to a true understanding of the arguments presented. It only exists to make it easier for other academics to guy and skim your book for your points, to search your citations and see if they agree with them or not, it is never about you or really your work. The Academic tradition is a snake devouring its own tail as the world around it has blasted into the 21st century it is wallowing in its own memory institutional filth. Every single problem with the system of publish or perish could end in a single generation but no one really wants to because that would mean the whole game they have spent years and money learning wouldn’t work the same way. The journal publishing houses are worse than the books (excepting textbook publishers). The continued maintenance and control of such non-entity hands would never be tolerated in any other University matter, but this one serves to reinforce the specialness of those publishing.

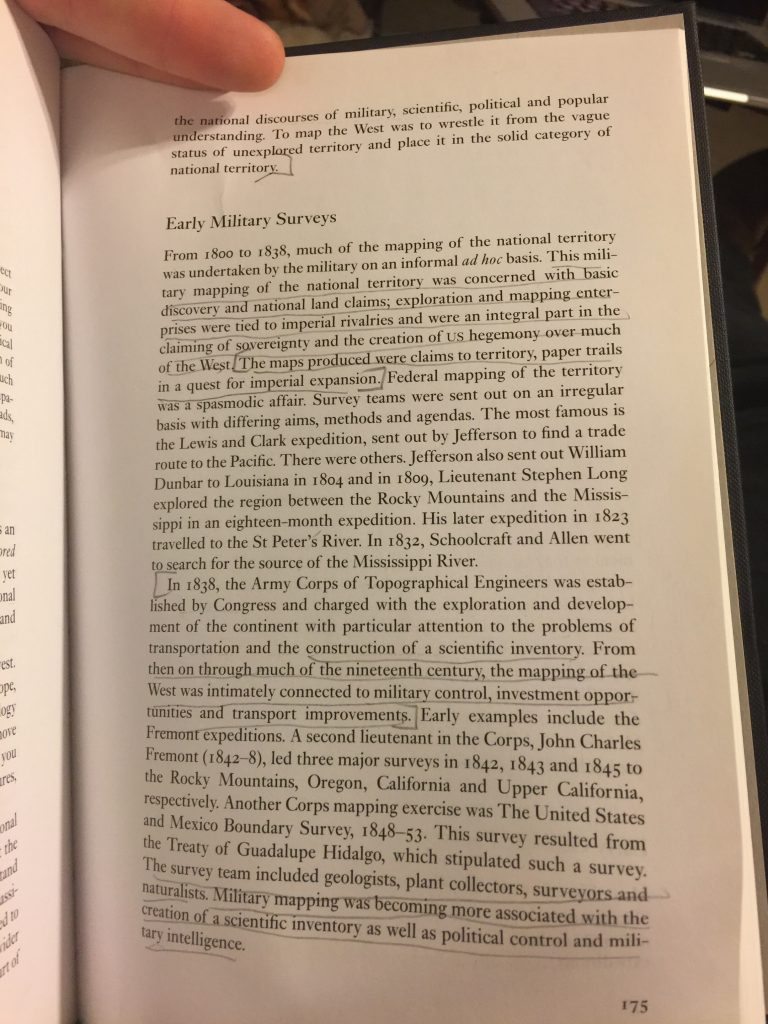

Following that arc, something that I found of great interest were the reviews for many of the books on my list. The first 1/3 of the sources (Natural History and the History thereof) was heavily reviewed, many with multiple, sometimes disagreeing, reviews showing up in a swath of journals. The second portion of works (American Studies) were less reviewed both in number and diversity of journals, possibly due to American Studies existing as this ephemeral discipline in many Universities. The third, and for my work one of the more important aspects of my exams (Art and Art History), was almost non-existent. Trying to place these works and artists in a historical context is an uphill battle when all you can find are a few gallery books, an encyclopedia entry, and maybe an “about the artist” blurb in permanent collection. More often than not the “reviews” I could find were from librarians whose sole purpose it was to recommend books for pubic libraries.

With those unpleasantries out of the way, I will walk you through the three days of testing and (skipping the three weeks wait) the oral defense. Our testing procedures here only recently changed. Before you would had to slog to campus by 8, get your questions, and sit in a tiny room with a computer with no internet access and type out your answers. (After all you have to prove what you know and like the language exams here, you would never ever access a computer or the internet during your research). Now, thankfully, the process is a little less draconian. You can take your exams wherever you wish, utilizing your notes, books, and computer (you know, as if you were actually a working scholar). You have your questions emailed to you first thing in the morning with your instructions on when they are due back. Then you write everything you know.

Mine were done on a Tuesday, Thursday, Tuesday rotation. Armed with a printed and bound collection of the book reviews I could find and the blog posts from here (I used blogbooker.com to export and print these notes) I waited for the first email. All three days worked pretty much the same way, I got up, did my regular morning routine or treadmilling and breakfasting before heading into our spare bedroom/office for my mission should I choose to accept it.

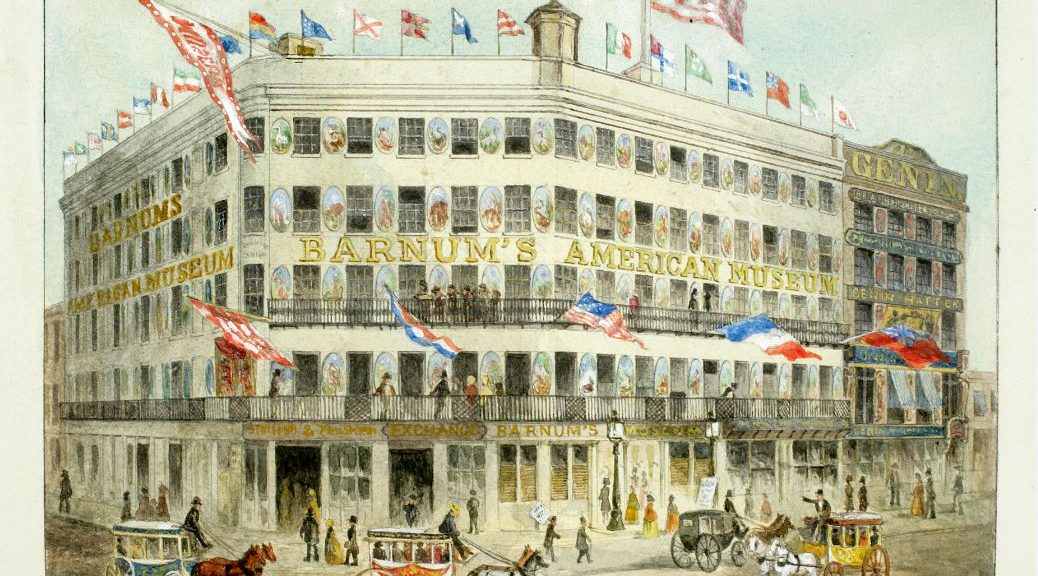

I queued up the entire season of Scooby Doo, threw on my headphones and started answering questions about the nature of 19th century nature and those who decided that what was. You can find the questions and unedited answers on the PDF page of this site if you want to spend some time with that. I started at 8 or 9 depending on the day, which meant they were due at 4 or 5 respectively. The way that I constructed the day was one part of the question, stop for lunch, tweeting my progress, and second question. This may not work for everyone and I talked to people that were too nervous to worry about food for the day, I don’t recommend that, but some people don’t have control on their anxiety levels.

My answers were around 6000 words in two parts, and I finished well before the allotted time expired. There are some spelling and grammar mistakes throughout (kind of like these posts), but I have always had this terrible habit of changing things when I edit, even when copyediting which defeats the entire purpose of editing. I have come to terms with needing a good external editor for things so they will be finished and correct before going to press.

–Three Weeks Laters–

I have a dream team of a committee and they are almost impossible to track down at the same time. This is one of the reasons the oral defense was so far away from that last “send” push. I like my committee and I have worked closely with everyone on it. I enjoyed my reading list for the most part too. I was looking forward to my defense, not because I was expecting to be grilled, but because the very people I learned the approaches to my work were going to be there to talk to each other as well as grill me. I was asked specifics on some of the more broad examples I used in my answers, I was asked about framing answers in a certain way or starting at a certain position (specifically the West as America for the beginning or the changes in scholarship answer). My answers were satisfactory, and I was indeed pushed to the point of having to say “I don’t know” which I have been told on several occasions is the main purpose of this medieval academic hazing process. Congratulations were given, signatures were collected, and the official paperwork was taken to the Graduate College.

And that is it. Pretty anticlimactic for as much time, energy, equity that was put into the preparations, right? The preparation is the key, the exams are just a formality to give the preparations an endpoint so you don’t continue reading one more thing for the rest of your life. For me, the next step is hammering out a prospectus. Mine will definitely *not* be a paragraph abstract. One thing that I hope to implement will be a digital component to the work. Originally I wanted to rework a website (not this one) for the U.S. Exploring Expeditions and the Pacific Railroad Survey Reports so they could be explored, remixed, etc. Now, I believe I have a better option that might actually be able to happen. My hope is to get good high resolution scans of all these journals and taking all of the plated out to create a huge digital atlas of the prints. The images could also be shuffled and arranged via meta data by content, location, type, etc. I will update that part of the project here as well. Until then it is back to the irregularly scheduled programming, and I have a couple ideas in the pipeline. As I start work on my dissertation, I will try to keep Sunday’s free for afternoon updates on that process and any other musings that come up along the way. This whole process was incredibly useful for me, and I don’t think I could have been as prepared for my exams had I not thought through the contents here and besides there is nothing quite like failing in full view of the public. Not only was it useful because writing is a way of thinking, but sitting down every week or so and hammering out an average 2000 word post was a great exercise in extemporaneous writing. If this whole process helps just one other person, it was more than worth it for me. I have gotten my use out of it, but maybe a first generation PhD student perspective on this whole thing will help someone else too.

~If you are interested to know, to answer all three questions I watched through all of the original Scooby Doo, Where Are You? season 1, and The Scooby Doo Show 1 and 3 (2 is short and bizarre) and got about halfway into Season 1 of What’s New Scooby Doo.