As this starts the downhill side of the list it is only appropriate for things to get weird. Since many of these literary, print, American culture books are from interlibrary loans, the reading order is currently being structured by when the books are due back to their respected libraries. The other somewhat bizarre occurrence is that the books are starting to all say the same thing. I would like to think this is due to some achievement of enlightenment on my part and not simply due to the fact that the only people publishing on this topic are the ones on this list. That being said it is getting harder to figure out how these books fit together in the sense that many of them use the same early secondary source and then interpret it slightly differently. I want to keep up the series here until I am finished with the readings and then I can go back and study through here and my notes, but I can see the usefulness starting to drop off at this point. Maybe it is just a lull, maybe not. Either way, I am keeping on keeping on.

Working honestly, when I saw the title Empire and Slavery in American Literature, 1820-1865 I was less than thrilled to undertake it. Make no mistake I know how important it is to student slavery in context, women and gender studies, under representative cultures, etc., but I have a hard time making sure I check each box on things that I write. I refuse to shoehorn asides of race and gender into a narrative if they are not part of what I am researching. Eric Sundquist’s book is delightfully not what I was expecting. I was expecting it to be this dry, matter-of-fact, treatise on representation of race and slavery within Literature and how imperialism was a misdirection of fools in power.

The greatest strength of Sundquist’s work is his dive into the primary sources. Something that seems to be lacking in many history seminar (and even some research methods) courses. He starts the book out by looking at letters, journals, and autobiographical accounts of individuals to construct a more personal view of the antebellum period with feelings, thoughts, logical interpolations on either side of these enormous but delicate issues. Many of these are the basis (according to Sundquist) for the development of chicano and Mexican literature in the American Southwest. The second part looks at American expansion as it roared over the American Indian and the outcomes of those dispossessed in the form of myths, tales, and songs transcribed by ethnologist, treaty and war orations transcribed by first hand witnesses, and “prose fiction by Indians or their amanuenses” (89). In the final section Sundquist turns to African American literature as well as works by abolitionist and those who were pro-slavery. The book is filled with little known, or unknown works that provide a more even scope of the literature that was circulating in the antebellum period and through the civil war.

I have had History’s Shadow: Native Americans and Historical Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century for a couple years not since stumbling across it during an art history course. The book is centered on the idea that the Native American question in general, and Native Americans in particular, focused American national historical consciousness during the 19th century. That analysis ends up (many times) revolving around the interplay between popular culture and the professionalization and specialization of academic disciplines. Moving from the art that allowed for the continued acceptance of the native peoples as all parts of a larger “vanishing race” Steven Conn follows the main theme of developing anthropology. Linguistics, and especially “objects-based epistemology” had evolved along with the artist’s brush and the archaeologist’s spade. By placing Native Americans into 19th century history instead of just (or only) 19th century anthropology, Conn breaks with longstandign traditions that kept native peoples aligned with their own history (prehistory) and thus vanishing in the face of modernity, and more importantly not being part of their own present. One important point was drawn for anthropologists by Regna Darnell in her review of the book. Her closing line reads, “For anthropologists, the moral may be that Native Americans had a history in American popular thought that preceded the discipline’s hegemony over them.”

The Rise and Fall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in Nineteenth Century America is a firm companion piece to a book we used in a undergraduate class sometime ago, and one I expected to show up in more places than this: The Wages of Whiteness. Alexander Saxton’s multidisciplinary approach to questions of race and white egalitarianism is ambition in method and scope. Beyond the politics of the developing political parties (and class) with the “soft racism” of the Whig party among the most interesting issues at hand, it is the mass culture that I found the most interesting. Specifically Saxton’s handling of the Irish use of blackface minstrelsy to establish themselves as white first and catholic second. By distinguishing themselves as something other than the other, they worked at become more of the same (from the ethnic white perspective). A simple take from the work could be that racism is far more than race relations. To expand on this a bit, the question of race specifically lies in the bedrock of the American (white) Republic and pervades through modern times with deeper roots, meanings, and expressions than any one perspective will ever unpack. Ignoring the other nonwhites the quasi-binary here is that nonwhites were incapable of taking part of republicanism because of the “natural” order of things. To wit: black inhabitants of America were too subjugated into bondage to ever be true participants in a republic while those with Red skin were too free.

Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California was the reverse side of the coin that I was expecting Empire and Slavery to be. It is a short book, and a quick read, but that belies the importance of the points that Albert Hurtado raises. Everything about this book boils down to mixing: mixed blood, mixed marriage, mixed cultures. For the most part it deals with the rations of men to women in California at any one time, specifically during the gold rush which caused more issues than it solved with throngs of men and only few of the “right” women to marry while Native, Mexican, and other “women of color” fell into prostitution in high numbers. Outside sex and gender, Intimate Frontiers is a strong, well written reminder that California is the best example to understand American frontier development. Those living in what becomes California were never a confederate band before it was infiltrated by Franciscans and then Spaniards en masse. From the earliest european involvement on the North American West Coast it was a mixed bag. With Mexican independence from Spain in 1821 the Spanish in California become Mexican, and then with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago they change again into Americans. All the while working within existing cultural hierarchies and patriarchies and things did not get any better when the discovery of gold brought in peoples from all corners of the globe. Areas like San Francisco were culturally diverese in people and architecture, it would take the a city demolishing fire to erase that footprint and see a more homogenous looking city in direct opposition to what the inhabitants exhibited.

American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture (notice a pattern of these subtitles?) looks at popular fiction as a means of understanding the expansion of American culture. Shelley Streeby analyzes dime novels and popular fiction as it pertained to things like the Mexican War. Some may be surprised at the sex and violence that purveys the 19th century texts that she analyzes, but it is as true for then as now that sex and violence sells books. But Streeby’s analysis goes further than the materialistic and looks at publishers political bents. Specifically George Lippard and how his catholic paranoia and desire to fight industrialism by empire building led to his books being filled with blood, guts, and sex. Even Lippard’s non Mexican War related texts were heavily Gothic in tone and were brimming with scenes of massacres, rapes, naked women, and sided with the class struggles with a position of damn the rich and champion the poor.

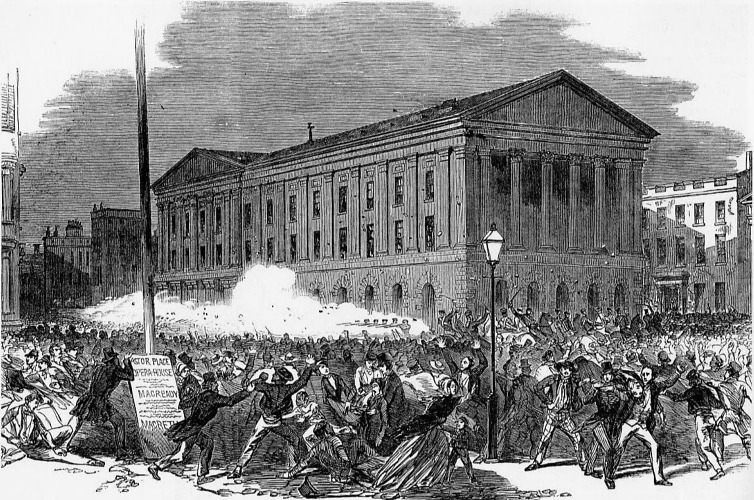

Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America should be read by anyone with an opinion on what consists of learn-ed culture. Lawrence Levine follows the decline of a rich, largely shared culture (or even a common cultural consciousness) from 1840s into the 1890s. He starts by looking at the popularity of Shakespeare within the public and just how well known the bard’s work was. The impetus for this pursuit came from the realization that many of the blackface minstrel jokers were parodies of Shakespeare, and you can’t pardoy what isn’t popular (or unknown). This is something I have thought about since learning that the stagehands on the east coast were largely made up of sailors on shore leave since they had a working knowledge of ropes, knots, and rigging. The idea that these sailors would be quoting and/or performing the plays while at sea has always made me smile. Levine’s work is the strongest independent confirmation that those thoughts might indeed hold water. It seems that is is the bifurcation of culture follows the development of those class stuggles that Lippard would have been writing about. Serious, learned, high, art and culture opposed the popular, vulgar, and low forms of entertainment. That Levine opened these doors and lines of questioning in 1988 it is sad that only a few scholars have attempted to follow up on them or go through them. Honestly I see more who are comfortable with their seat in “high” culture that would like to close the doors that Levine opened. This is the problems that Whitman and Poe were lamenting, that they never reached the people. Their work, Whitman’s especially, while about the common man were adopted by the quasi intellectuals and discussed out of sight of the public. Twain, on the other hand managed to tap into that popular mass with a loss of potency of his social criticism. There are reasons you won’t see a Norman Rockwell exhibit at the MET even though it would likely be one of the most attended in memory. The problem is, as Levine quotes in the end “The public is an ass” and it is exactly those asses the MET doesn’t care to have en masse at the sites of high art. This book is paired usefully with The Temple and the Forum from last week. To cite a modern example, what Levine is describing is exactly what happened to the music of Tracy Chapman in the 1990s. Her songs, mainly about lower class minorities, found its strongest fanbase in white middle class suburbia. The people that make culture define culture. As I have gotten back into comics since starting work towards a PhD, I recall several honors English courses at my undergrad alma mater that utilized graphic novels for literary criticism. Much to the chagrin of some members of the faculty, how can you waste time teaching with such aspects of popular culture. As Levine implies, you always have to say “popular culture” with a sneer, because anything popular can’t possible be useful except in all the cases illustrated through the books in this section.