I was most recently tagged in one of those social media chain letters asking to produce a number of books that make my “good reads” list. I saw someone else post it the day before as the 10 (I think) books that changed your life. I think about these whenever I see them, even if I am not tagged, but being tagged with a separate set of list instructions really put me to thinking about reading, and the books that I have.

|

| My library. Really choose only a handful? I have read completely about 75% of these. Most of the rest are for reference. |

For me, at least, I find it hard to not say that every book you read has changed your life. That impact may be imperceptible, but just as you can never cross the same river twice, you cannot possibly be the same person you were after finishing a book. Whether you loved it or hated it, or even didn’t finish it, it has left its mark upon you in some way.

In an attempt to be reflective on my own reading experiences as well as subversive to the Facebook list chain letter that I am sure was started by a poor unfortunate Nigerian prince just before he set out on the ill-fated journey in which his car wrecked and he left a sizable inheritance to me, I will do both, but with my own rules and parameters.

There are the classics that I have read, because in my 5th grade mind, the classics were what everyone should know. I tackled Moby Dick because it was huge. (If Charlie Brown could read War and Peace, I could read Moby Dick) It was a herculean task for the summer between 5th and 6th grades. I had already read 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea because my grandfather had said it was his favorite book. I have read it at least twice since then and I find myself still sympathizing with Nemo. To be honest I was in awe of Captain Ahab’s blind ambition to a goal, damned the cost of life, limb, and/or money. I think that is because I never had anything that I was that passionate about. Even today, people that fuss over a certain show, a certain book series, or a certain pop culture entity both fascinate and on some basal level repulse me.

To this day The Wind in the Willows remains my favorite book. I have watched the identifiers change from the simple enjoyment of anthropomorphized animals to the underlying struggles of class and even race. But, at its heart it is really the talking animals that do it. The companion piece of animation produced by Rankin and Bass is my favorite animated feature as well, even if it does rearrange the characterization a bit. Don Quixote continues to be a favorite for Cervantes writing style and most especially for his humor and use of irony and dialogue. H. Rider Haggard’s stories of Allan Quartemain and Conrad’s Heart of Darkness were also books that are still floating around in my brain mixed with a more than healthy dose of Ernest Hemingway.

Once upon a time Wal-Mart ran a “complete and unabridged”series of the “classics” that were two for $1.00 in paperback. Since my mother worked there, I was able to get most of them and they certainly came in handy. Fred, Texas only has an elementary school and come jr. high and high school we were bussed about 16 miles to Warren. When school let out at 2:45 I still had an hour and a half before rolling in on our dirt road at 4:30. I read on the bus. A lot. All of them. I can distinctly remember reading Rifle’s for Watie, Johnny Tremain, and the True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle as well.

One of the most influential books on my mind’s eye and judging the realism (real and imagined as I later found out) was a book in this series given to me by my grandfather. It was Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage. Ever since I read it and learned more about Crane’s life (what little there is to know) I have always had a kind of soft spot for him. But the vivid details he put into his writings still stands out to me. Of course, Jules Verne and H.G. Wells still come up again and again (to my utter delight) as characters influencing the history of science.

|

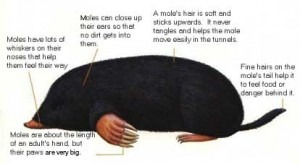

| Geology AND geologic time |

I made the same grown up transition that many do and read Michael Crichton starting with Sphere in 6th grade until I ran out of his books. Jurassic Park and Congo are still favorites, and forgetting the terrible movie version, Timeline is a surprisingly good book.

As far as the books that have “changed” my life in the sense that the questionnaire wanted to know so they could target my page with advertisements for things the algorithm relates to those titles there are two sets that I have that have influenced my particular path of education and study. Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, which I read not long after beginning college at Lamar was a beat up library copy of “the books that inspired Darwin.” They are actually beautiful pieces of literature aside from important technological geological ideas. I recently found a very nice leather-bound set pictured with the other set that has influenced my studies greatly.

Somewhere on either side of my birthday in the year 2000 my grandmother gave me a millennial edition of the Rand McNally road atlas of America and said “use it.” It took some time but I eventually took jobs that required travel, and when I finally went back to college used it all over the American southwest on geological field expeditions. Some time after that she gifted me the leather-bound set of the Lewis and Clark journals along with Stephen Ambrose’s Undaunted Courage.

I sat in the back yard this morning finishing up reading and some research on the Pacific Railroad surveys for one of the first (last) classes I will take before writing my dissertation. The challenge to list influential book has come at an interesting time as I see the list of names and contributions to American history that follow the geological pioneers that accompanied the first surveys west, including Lewis and Clark. Even re-reading Turner’s Frontier Thesis brought into focus several geological analogies that I had missed the first 5 times it was assigned in American History.

The history of the United States, especially the American West, is indelibly linked to the history of geology, and almost the entire nation has an inseparable link to the history of science. Most en vogue historians of American science begin our ascent with the Manhattan Project, ignoring the vast wealth of scientific history that predates the birth of their favorite emigrant scientists. The more diverse places that I look for our history, the more often I see familiar names, Hayden, Powell, the entire Peale family, Baird, and others with government reports being the largest body of evidence for their work. We cannot break the early ties of government and scientific expeditions, and somehow through a very winding path, all roads have converged to the point where that needs to be written, comprehensively as a historical work on science, art, politics, religion, genocide, and culture. That is where these two sets have led, and why they would be some of the most important works I have read.