Welcome back to the “teach yourself literary criticism in 12 easy steps” portion of this endeavor. This will actually (likely) be s shorter than average post as almost half of the readings subdivided here were companions or intros to Poe or Twain. The differences in which are interesting themselves and something I will come back to at the end.

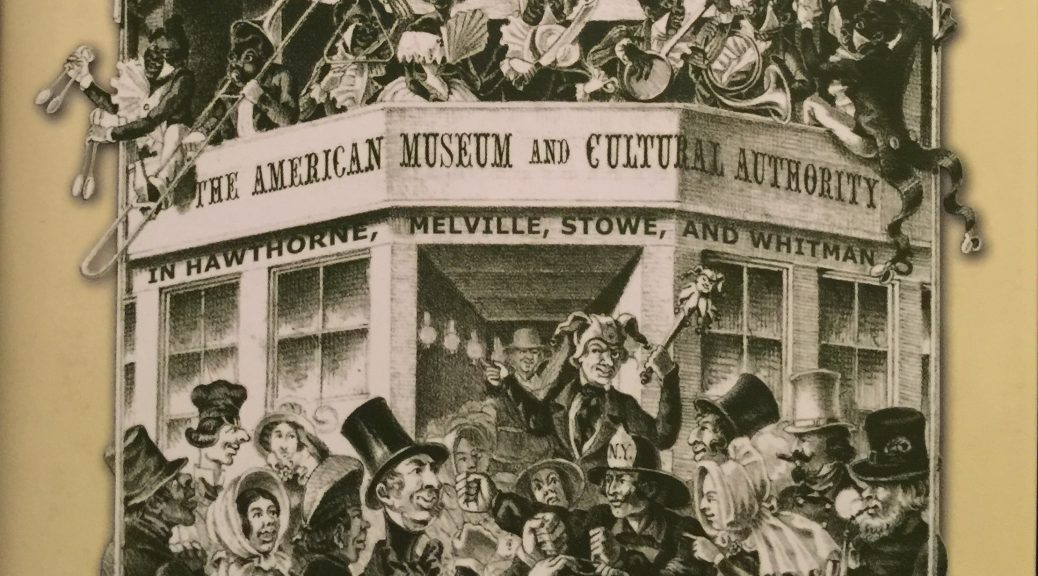

The first at bat here (world series between the Indians and Cubs is currently underway) is a holdover from when my rough lists included much more about the history of display and museum culture/theory. The Temple and the Forum: The American Museum and Cultural Authority in Hawthorne, Melville, Stowe, and Whitman will be one of those books I try to teach with in the rare event there are any tenure track positions available when and if I survive all this. Les Harrison looks back at the developments of three “American” museums: Peale’s, Barnum’s, and the Smithsonian. The idea of democratic, or even public, discourse is shaped by the architecture of these buildings and the cities where they reside(d). The temple is filled with reverence for more than holy nature, but it is the paramount example of unidirectional authority. Specialist (or at least the initiated) were the ones dispensing and recollecting the order of nature. The forum on the other hand was (and is) the bustling arena for opinions, thoughts, private enterprise, and in some of the examples of Barnum: the popular, the bizarre, and the humbug.

But, it isn’t just about museums. The subtitle is your pocket-seized who’s who of American literature. Hawthorne emerges as the showman shining the spotlight on the tensions between the temple of the official history and the forum of fiction. Interestingly, Harrison sets Melville’s Moby Dick up as a confrontation with both the temple and the forum for the manner in which both were being controlled and shaped by Ahab-esque showmen. Stowe’s work seems to follow the same arc as the museums–from a Peale light narration through the stage plays and literal exhibition in the forum of theatre in not one, but two extremely popular forums in New York alone. Wrapping up with Whitman Harrison situated Specimen Days under the complete iron dome of the capital building finalizing the United States growth politically, scientifically, and through much personal exertion on Whitman’s part, culturally.

A Fictive People could follow a few paths, but its subtitle Economic Development and the American Reading Public set out from the cover to explain the impact of such things as high literacy rates, improved printing technology, new schooling systems, and the “cult of domesticity” had on the “golden age of reading.” This isn’t a cause an effect history. It is almost the opposite. Ronald Zboray moves from the earlier travel records of Europeans visiting America through the merchant travels of booksellers and increased publishing all to show that far from democratizing the populace, economic development actually exacerbated the regional differences within the country, and not just in literary tastes.

Even after the development of a book trade, distribution networks were still differentiated by region, tastes and consumption (of potable and non potable goods) remained stratified by class, colonial preferences still remained (even if dress in new post colonial clothes). On the other side of the analysis Zboray reveals that reader’s tastes were not as radically divided aling gender lines. It would appear, to paraphrase someone we will be talking about later, that the arrival of a “mass literary marketplace” in the 1850s have been greatly exaggerated.

Understanding American literature in the antebellum, and most of the post-bellum period means understanding the entire cultural context of the United States. This is true for American Science, American religion, American art, and American Apparel. The collection of essays in American Literature and Science (ed. Robert Scholnick) cuts a cross-section through the period with a host of well-known American men of letters. During the early republic science and literature could be pursued together in the cases of Franklin and Jefferson. The growing schism between the two towards separate specialties and professions are chronicled by Thoreau, Poe, and Emerson among others. The essays fall short of the modern period, although Scholnick does mention modern essayist such as Stephen J Gould, Lewis Thomas, and John McPhee at varioud times in the introduction. The later chapters highlight how science and literature still speak to each other, sometimes subliminally, across the rift that is modernism. In the closing essay N. Katherine Hayles discussions (airs her justified annoyance) that most of the science and literature literature focuses on how science influences (or influenced) literature. In the end science, like literature, is a cultural construct and both of them need to be considered (and understood) as two sites within a complex cultural field” (229).

Walt. Whitman. I have never especially cared for poetry. Sometimes I still have a bit of an issue with the fact that it is perfectly okay for it to not rhyme. So, coming to Whitman as a cultural icon instead of an iconoclast probably sets me at a disadvantage when considering his mark on American Culture. Luckily David Reynolds (we’ve discussed some of his other work before) has a giant horse pill of a book to help reposition Whitman within a broader cultural context (sometimes created by Whitman). Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography I think is less about Whitman’s life regarding Whitman and more a biography of cultural told through the development of Whitman. This is like thinking that Anne Rice just wanted to write books about world history and decided that the immortal undead is the best vehicle for such.

Reynolds takes down this notion that Whitman is America and American is Whitman. I was unaware that this was the case. This was my first exposure to Whitman’s bohemian ways endearing him as America’s native son. Good thing, because it turns out that such a notion isn’t entirely true. The overall arc of Whitman’s life fits with the arc of American culture. His best plan was living longer than many of his contemporaries. For many of the cultural monoliths we do not have baselines for comparison pre and post civil war. Reynolds begins and ends the book with Whitman’s 70th birthday to show that the zenith of the American Cultural celebration for Whitman coincided with the author’s largest absorption of capitalism and self promotion.

The middle bit of this nearly 700 page handbook to the 19th century is filled, sometimes to overflowing, of analysis or art, literature, and science. Similar to Reynolds other work Waking Giant it borders on sensory overload for the reader but provides a familiar avenue to access Whitman for nearly anyone. Reynolds also uses the same high school yearbook type run of portraits in the center of the book. He also includes some of the art discussed as corresponding (in most cases 1:1) with lines of Whitman’s poems. The Alfred Jacob Miller piece is striking because I blogged about it for an art history course and I will be taking up studies of Miller in a few weeks. Maybe this means I am on the right track. When Whitman’s likeness is used for cigars it is more or less proof that he has become American culture. Reynolds, and perhaps Whitman himself, believes that this was less than what Whitman was hoping for. Even at the end of his life Whitman lamented not getting through to the “people” and being a more powerful agent of social change in the the world, especially after the Civil War. As I stated earlier, I think that to follow Whitman through the 19th century is to follow American Culture through the same.

Poe and Twain. I am not sure this isn’t akin to that Beatles or Elvis question from Pulp Fiction. That is to say that you are one or the other. You may be an Elvis person that likes some Beatles stuff, but you can’t be booth. (Man, there is a lot of italics emphasis in this post). Is it the same for Poe and Twain. It seems that way, but then you can break it down farther with Poe. Do you prefer Poe’s poetry or prose? I have always preferred the prose with the exception of The Raven and Annabelle Lee. Again this is how I came to Poe first, so reading in these companions that it is only recently his fiction has become mainstream, is a bit of a shock.

Poe, whatever his faults, seems to have always had his finger on the pulse of American Culture. Like Whitman’s lament Poe never really reached the “people” either, save the immense popularity of The Raven. (he even wrote that the bird outdid the bug, in response to the poem overshadowing his most popular prose The Gold-Bug). He is seen as a hoaxer with Hanns Phaal and Balloons, or MS found in a bottle. He was also an astute critic in the press, much to the detriment of his personal amicability. His science work may arguably be ancestral to science fiction. With Eureka, which was dedicated to Alexander von Humboldt, among others being prescient into the 20th century. His satire of Egyptomania and deferment to science in “Some Words with a Mummy” is one of my personal favorites.

Back in American Literature and Science the Poe chapter looks at his use of Newtonian and Platonic theories of optics. Looking and seeing is a lasting distinguishing theme in my own work, probably only second to authenticity and authority. The work here allows for both Newton and Plato to argue the same case. Newtonian optics for the actual mechanical process of looking, and more or less sight, while the older “untrue” system is where the seat of imagination and actual “seeing” comes into play. This is the type of thing that give examples to Poe’s brilliance. There is almost no escaping tragedy in Poe’s life, some self-inflicted, most beyond his own control. Poe, defining, or defiling genres is at his best and the most tragic thing for American literary culture is that he died in the middle of it. Better known, if not better appreciated in Europe it seems fitting to end with the modern cliché that he was known as a genius in France.

Mark Twain. Use this in its actual working context and know that the waters are dangerous and shallow here. Twain is one of those people that are eminently miss-quotable for any occasion. Think of him as an American Oscar Wilde. God, he would hate that. You can’t get out of the American school system without getting Twain on you. Unfortunately it is always the same stuff and it is getting harder to wash off. I will stop here to say that to a certain extent I love Twain and have fond memories of reading things that aren’t Tom or Huck related.

Twain was a humorist. He was funny, and that is exactly why he has endured this long. He is still funny. The reason that he is have less to do with his prophetic ability and more to do with the stagnation of culture. I think Twain remains popular because of the massive amounts of anti-intellectualism that is injected into his work. We still have a culture divided over book-learnin’. On one side, it doesn’t teach common sense, but on the other it doesn’t elevate to the levels of pretense that some like to subscribe. If Poe was the pulse of culture Twain is the pulse of class. The companions and introductions all treat Mark Twain as more than a pseudonym. Samuel Clemens needs a vehicle to travel through the frequently disunited states in order to make reports back to the reader and it not be a personal affiliation. This adds great strength to the ideas brought forth in Fictive People.

Twain’s “hoaxes,” humor, or satire always tend to attack the establishment from the outside. Always the outsider, similar to that honed identity of Whitman and practiced nature of Poe are the hallmarks of Americana. Twain reached the people that Poe and Whitman missed. This seems mainly due to the popular press, and the reading public’s penchant for fiction. In the end Twain spins a good yarn, even if they follow the same model and employ many of the same tropes.

There were others writing satirical humor against science and culture, but it was done from a different background, most notably George Derby. Derby was West Point stock from the immortal class of 1846 with Grant, McClellan, Pickett, and Stonewall Jackson. A student of science, Derby, under the name John Phoenix, skewered the plethora of “official report” literature coming in from the American West. Derby makes fun of the scientists Twain makes fun of the science. Derby’s surveyors serve the same purpose as Poe’s (and Locke’s) hoaxes: they are warnings against uncritical acceptance of “facts.” Twain makes fun of the science, and uses that to later launch personal attacks on the likes of O.C. Marsh for mishandling federal funds finding birds with teeth. More attacks on science (specifically paleontology and the “fossil craze”) in Twain’s “Petrified Man” are hard social commentary. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court presents and even more dire portait of the unstoppable juggernaut of American technology. These aren’t just stories for stories sake, even if they do get absorbed separately from their social warnings.

Understanding more about Twain has led me to realize why I only like some of his work now. Like Poe it is usually his lesser studied (or assigned) works. A Tramp Abroad is one that comes to mind immediately. Although I have a full collection of Twain’s work, I always find myself skipping over Tom, Huck, and Pudd’n Head for some of the more entertaining collection of essays. The best analogy I can find for moving beyond the adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn is when you finally outgrow Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Sweet Home Alabama. Even with their works tilt the same way their methods and means are still markedly different. Twain’s Yankee modernizes (and ultimately destroys) King Arthur’s Court, while Poe’s mummy offers a retort for every piece of ‘modern’ life, save on. The ultimate production of American society, industrial, economical culture is the cough drop. That is probably why I like that story so much.

If you are unfamiliar with Beakman let me bring you up to speed. There are many overlaps in production and what networks wanted was pretty similar, but it wasn’t–and isn’t– a Beakman’s World vs. Bill Nye The Science Guy world. It goes way back to an earlier program called

If you are unfamiliar with Beakman let me bring you up to speed. There are many overlaps in production and what networks wanted was pretty similar, but it wasn’t–and isn’t– a Beakman’s World vs. Bill Nye The Science Guy world. It goes way back to an earlier program called