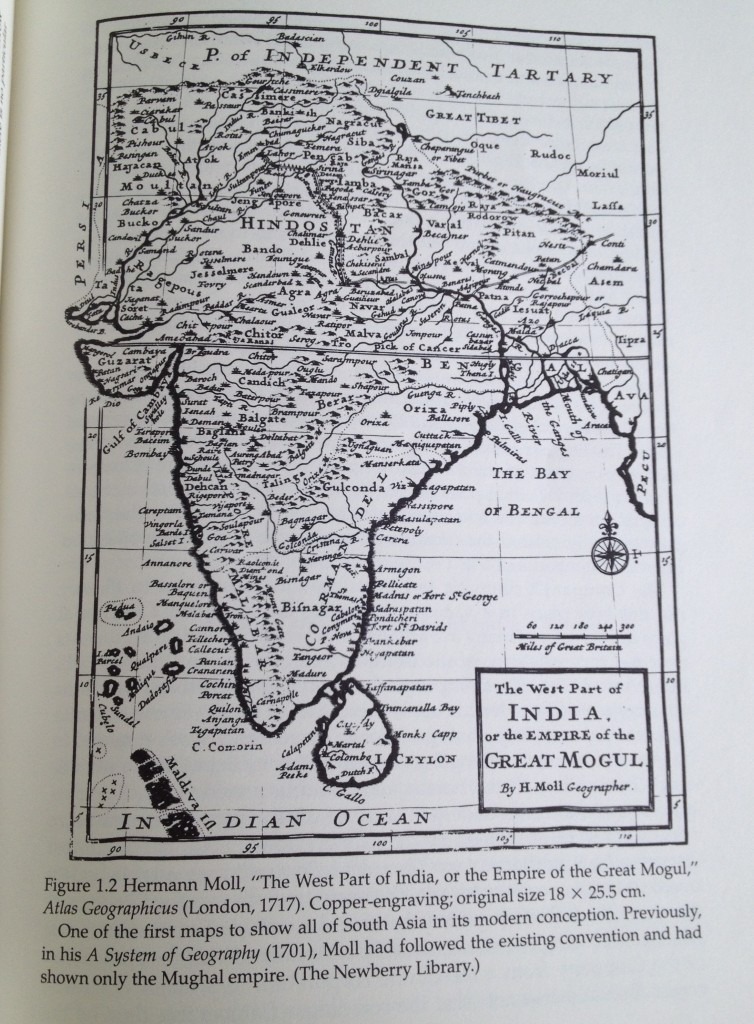

Matthew H. Edney’s book Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India 1765-1843 is not a book one grabs to read before bed. In fact it is almost impossible to digest in the week that we scheduled to discuss it in my directed reading meeting. It is, however, an excellent text book on the history and science of surveying and construction of empire. I mean the latter quite literally on paper (maps) and ideologically (colonial minds so to speak). That being said, it is difficult to provide a simple overview to that Edney’s work is all about. One one level, a base level if you will, it is about mapping. It is also about colonialism, empire, governance, surveying, and more precisely control.

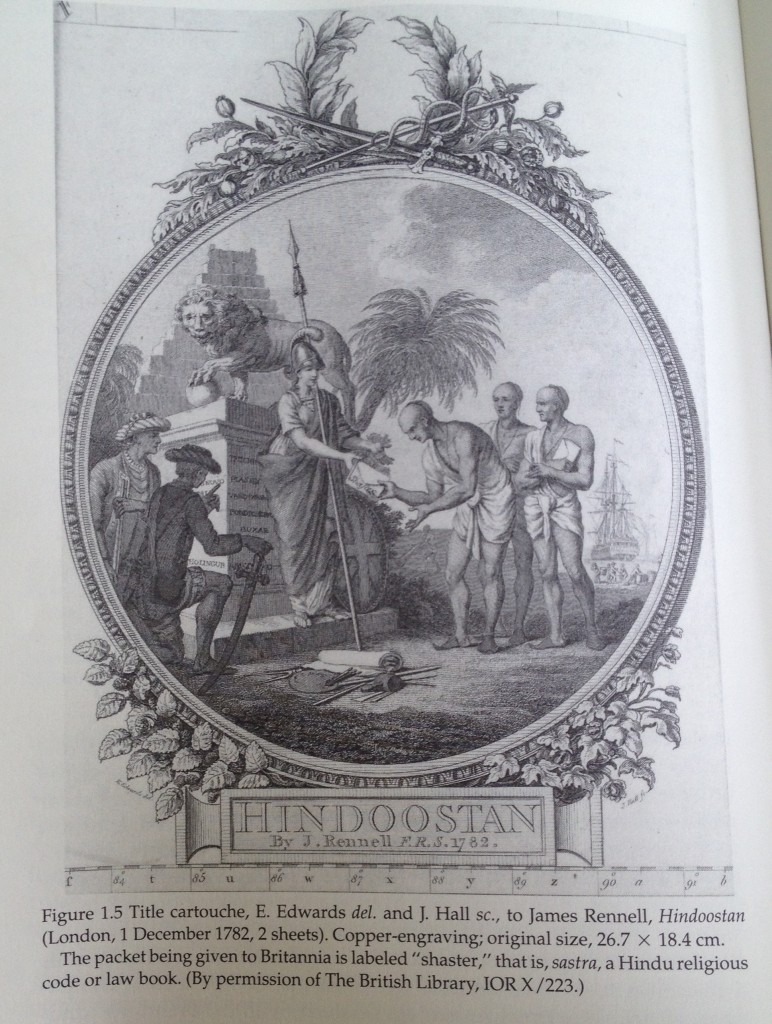

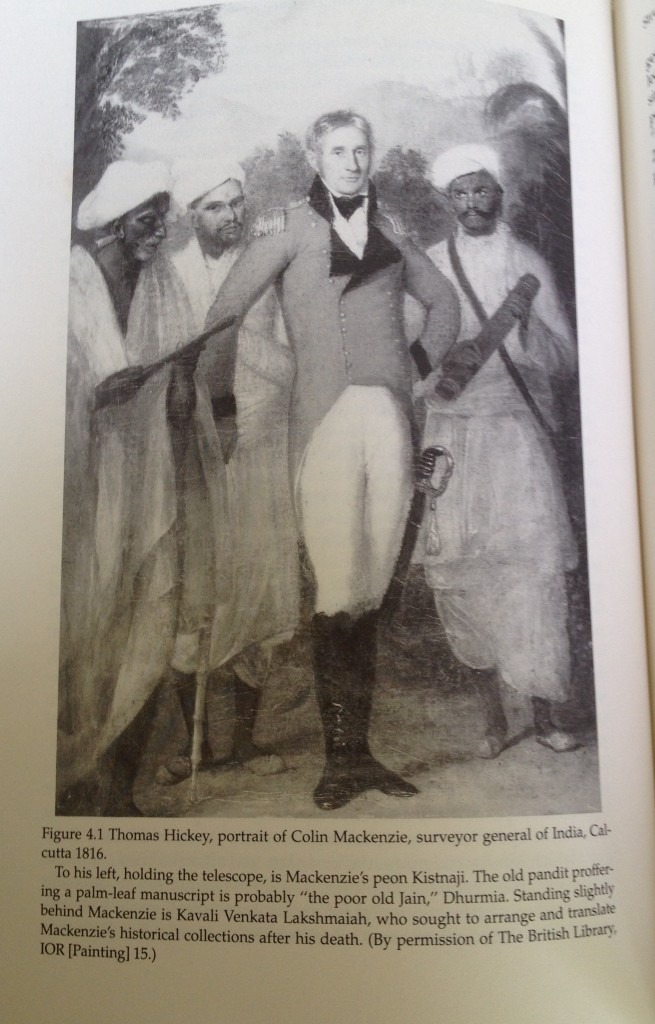

It is surprisingly short on illustrations, although the few it has are excellent. It provides a nice overview to what he calls “A Spatial History of India.” He takes it from the ideological roots of mapping and space representation through to the hard on-the-ground creation of teams that surveyed and marked up the subcontinent into something economically and empirically (and Imperially) useful. What may come as a surprise (or not, depending on how familiar the ready is with Indian history) is that the institutionalization of early colonial India was, in many ways, re-appropriated during independence. Edney does well to distinguish between British India and India proper early on. There are also tedious notes in the introduction explaining the exchange values of British and early Indian currency in their historical values and what they may (roughly) be translated into today.

To take full advantage of this book, it should be taught over the course of a semester when there is enough time for in depth analysis and discussion of the myriad of points made about India, British India, and “Cartographic Anarchy.” If you do plan to use this book in class go one step further and pair it with D. Graham Burnett’s Masters of All they Surveyed. Both books are from University of Chicago Press–Edney’s in 1990, 1997 and Burnett’s in 2001. The baselines are the same and while Eden’s covers India, Burnett’s looks at British Guyana and surveying in the South American colonies. There are numerous areas of comparison available to see what exactly was standard policy and practice and what was changed because of the idiosyncratic problems surveys and (colonial) government officials faced on the ground.

I picked up Masters of All they Surveyed back in 2008 to take along on an archaeological field site/school in Belize ran by the University of Texas-Austin. Like Mapping an Empire it is now a casual read in the jungle field diversion. I described to my field colleagues (who were reading things like Rosetta Key by William Dietrich) as reading someone’s dissertation. Because of the surveying I trudged through it, and in spite of the work, enjoyed it. Moreso now as I see how it follows Edney’s and was one of the books suggested for this reading series.

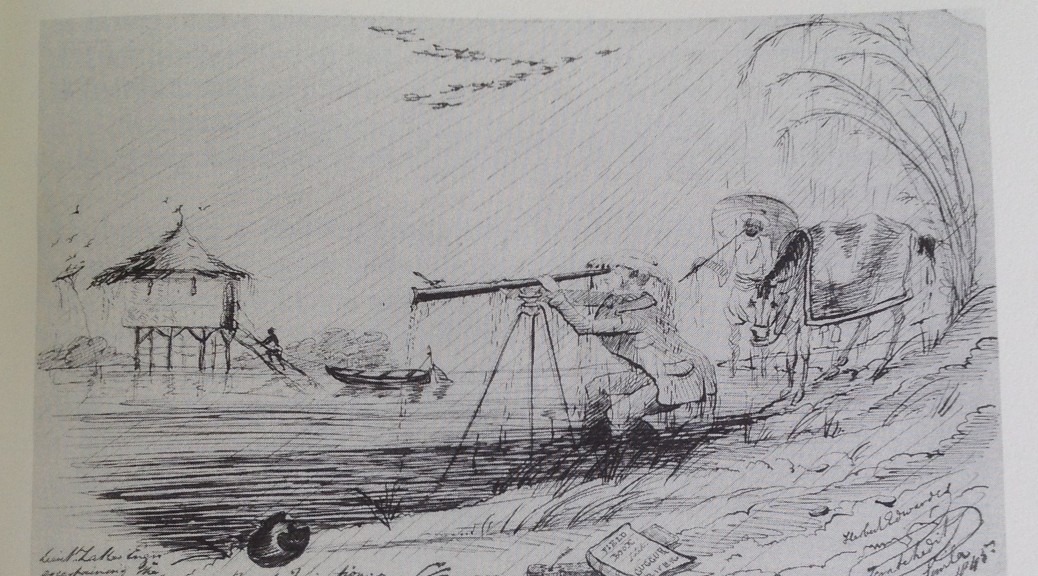

The surveying is what hooks me to both of these works. I actually worked as a surveyor during the time I was between going to university. I also worked as a carpenter (which I had done since I was 14), and a boilermaker, but so far neither of those has really permeated colonial science culture). The company I worked for mainly shot right-of-ways and roads for oil well pads and the like. Before I started, one of the owners (who, incidentally, I found out later had went to high school with my grandfather) was an expert witness on the boundary dispute case between the US and Mexico. One of the guys on my grew was the GPS holder for the survey that established the final boundary. He said the work consisted of holding the GPS staff on the US side of the Rio Grande, taking a reading, and then wading to the Mexican side for another reading. This is exactly the same sort of thing that Edney and Burnett talk about in their books.

The process has not really reduced in price either. The total stations, which are a vast computerized and laser improvement to the early British surveyor tools are still hundreds of thousands of dollars. These are one time purchases for a surveyor tool that costs more than a house. Further ironically, having put off posting this until the weekend, my TimeHop app showed me some posts from a few years ago when I was talking about that very job. What had sparked the memory then was a trip to the Norman downtown Post Office next to some of the city buildings. There in front of city hall as it were is a statue of Abner Norman for whom the town is named. It is a fantastic statue with the man carrying the tools of the surveyor’s trade.

The power of surveying and mapmaking cannot be overstated in cases of early colonial power markers and even modern international borders. They are emblems of order among natural chaos, they are tools or empire as easily as rifles or steel propellors are (see Headrick’s early Tools of Empire). Of all the work that was put into industrializing and creating a colony from architecture to agriculture it is all based on the backs of these early ground expedition crews. My own research looks at the same men working for, first, the Railroad Surveys, and then the USGS surveys, as they marked out the American West. Maps and Empire lie at the heart of the artifacts and authenticity world that I have slowly built around my work. It is almost as if the surveyors and mapmakers could fall into the hipster class of imperialists. They were there before the merchants, before the buildings, and if it weren’t for them getting into things at the “indie” level (some with government backing–and instruction) you would not have even known where to sail your trading vessel.

All this focus on Britain “out in the world” really belies the argument that it happened here in the US as well. Most people see American History starting in 1776, but it actually goes back much further than that even for just the white people. One of the interesting things is you can follow the same carving up of the North American eastern seaboard in much the same manner as Edney does in India and Burnett does in Guyana. They were products of the Empire as well. I am sure there are the same instances in Australia, but I am not as familiar with their history as I probably should be. To that end I will close with a song that highlights that same struggle and impact as are in both of these books. The song follows two members of the Royal Society as they sail to the American Colonies in order to establish an authoritative line in a border dispute between Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. The Mason-Dixon Line has become a “dead metaphor” in the US and is more of a cartoon (or television in general) trope of the line demarcating “Yankee Land” from “The South.” It behooves us all to remember that we are not separate form this process, but are fully influenced by the very same policies that shaped British India and British Guyana.