The final installment of these representative studies works means that I am onto the final third of this monstrosity. This far into the project has led to the interlibrary loan due dates shaping the reading order which, at first, looked like it would throw a couple odd books out from the main theme of the post. Fortunately they all talk about the same thing in some form or another so they aren’t as disjointed as it looked on first arrangement.

That isn’t to say they all fit together seamlessly. I will start with the full odd man out in this section because it is so narrowly focused on material culture in method and practice that it doesn’t flow with the broad antebellum cultural analysis that make up the rest of the books in this section. American Artifacts: Essays in Material Culture (edited by Jules Prown and Kenneth Haltman) contains a selection of essays written by Haltman’s graduate students while he was at Yale. (he is currently at the University of Oklahoma where he teaches a version of this same class. I have talked to him a couple times about his book on Titian Peale Looking Close and Seeing Far). These are detailed analyses of seeming random objects. The swath of objects to pick from ranged from cigarette lighters and telephones to photograms and stoves. The essays themselves serve as great examples of how object analysis can be effective on nearly any object. Prown would argue any object, but, for me sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. That is most likely due to my training in Archaeology. The way this collection is organized makes it perfect for teaching these concepts to graduate students or a group of really dedicated undergraduates. Haltman’s introductory essay outlines and summarizes Prown’s own articles about material cultural. Throughout Haltman breaks down and annotates the steps in Prowns syllabi. This collection is less about the objects and more about the training and ability to analyze these objects. For me it was interesting to see the close study of objects that have known uses, since most of my work with Maya artifacts consist of trying to figure out the use first and then trying to work on the symbology of form.

Roderick Nash’s Wilderness and the American Mind is about as broad an analysis as you can find in an academic text. Since it is in its 5th edition, it likely has a life as a textbook for conservation and environmental history, of which, according to one of the book’s cover blurbs, Nash is one of the inventors. It makes sense that it would be as there have been many movements and cultural pendulum swings since the first edition came off the press in 1967. The whole idea of the work is to look at wilderness as a concept, ideology, and new vocabulary. Nash starts with an anecdote about securing his advisor who suggested that he try biology or geology to study “wilderness.” It is the “American Mind” part of the study that is important. Nash breaks down the idea of wilderness and how that shaped the formation of cities in the colonies as well as the expansion west. For Nash, wilderness mattered mostly to the early Americans who were developing ways to clear it. To make it less wild. Exploitation comes later, and throughout the subsequent editions the sort of guilt first seeps into members of Nash’s generation. The bottomest of bottom lines in Nash’s work is that wilderness needs to be understood as a mental concept and social construct as much as (more than) a geographical space. The bulk of the book is a collection on literary, history, and cultural analysis revolving around how Americans described, constructed (and deconstructed) the wilderness and wild spaces that were part of the shared experience. Nature itself is hardly “untouched” or “pristine.” The idea that Native Americans were less perceived as humans interacting with nature and more as part of the wildness of that space is a key point for Nash, an explains much about the relationship between “Americans” and “Native Americans” which were in fact “indians” in the sense that there weren’t “Americans.”

Interestingly enough Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West by William Cronon does something similar with “the city.” The opening of the book describes his own mental constructs of Chicago in the very same manner that Nash observed with Americans and their wilderness. Taking on Chicago itself Cronon illuminates the cities importance in shaping the 19th century flow of trade of wheat, beef, and lumber. All roads may lead to Rome, but all railroads lead to Chicago. This has been studied before, but what Cronon does is follow the railcars back out of Chicago and how they interacted and shaped the markets outside of Chicago, the state, and even the region (The Great West being more of an extended middled west by the modern geographic regionalities).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dd3btVhwr48

“First Nature” and “Second Nature” come into play to mark the changes in the landscapes around Chicago and its suburbs. Outside the larger analysis some ket points of interest for me was how railroads went from boon to bane for the city as its population grew. Railcars carrying trade goods or people all traveled at the city’s grade level and the hundreds of pedestrian rail deaths became part of the ebb and flow of city life. To protect the citizens the city slowed the trains which slowed trade. Even as people began utilizing the rails to get out of town Chicago became a passing point and less a destination. Every passenger line came into Chicago on one side of the City and departed it on the other. The express was less so and as other lines were built to the South more people travelled alternate routes west. Chicagoans shaped the urban getaways of Michigan and Wisconsin as trains took them out of the city and out to the lakes regions for vacations and extended stays. Even Cronon’s grandparents lived on the lake. Reading the two together it was interesting to see how Nash’s wilderness was shaped into Cronon’s Metropolis, and that metropolis reconstructed the wilderness (As cultural concept that equals “not in the city”) again. That is not to address the fact that Chicago meatpacking industry (of The Jungle) fame led to the demise of the west as a buffalo market and firmly into a beef one.

The lumber trade was a interesting analysis for me since I grew up in lumber country in the Pineywoods of Texas. Many people made their wealth in Southeast Texas by lumber, without the existing market i a city the size of Chicago. There were rail systems to Galveston for transport to market until the 1900 hurricane. Which shifted industry north to developing Houston and later shipping canals and interwater ways make it similar to Cronon’s Chicago in the south. The dirt road I grew up on was an old logging tram that was abandoned after the lumber was harvested. After heavy rains it was common to find railroad spikes washed out of the sand. This is a perfect synthesis of Nash and Cronon’s work. My great-grandfather was a linemen for John Kirby enterprises that brought electricity to the “Kirby Camps” that popped up across the landscape where workers lived as they worked the timber. Many of which went on to become established communities (Woodville and Kirbyville, for example). The Starks made their mark in lumber and their home is now a historic landmark and museum in Orange, Texas and their private art collection-containing an original double elephant folio Audubon- lead to the Stark Museum.

John Sears’ Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century is one of my favorite books about this period. It covers a wide array of natural and manmade spaces that people travel to in order to visit. Niagara Falls, with its proximity to the east (and north) of the original “settled”areas of the continent was one of the first tourist attractions. The size of the falls and the geology of the area were evidence of “the sublime.” As travel became easier and the falls were harnessed for hydroelectric power the space became a tribute of the advancement of technology and man’s power over nature. In a sense it became the avatar for the sacred and the profane–less so because of the hydroelectric turbines and more for the shopping malls. Mammoth Cave was a near antithesis of the falls since it was absent of the sights and sounds, smells, and other sensory experiences that made up the visit to Niagara.

The whole idea of “Sacred Places” is that Americans had to find natural phenomena as exemplars of cultural achievement. Without the vast cultural history of Europe, the stylings of wealthy aristocrats and their private collections Americans turned toward their (and Nash’s) “wilderness.” As the century progressed, man made areas such as cemeteries morphed from simple burial plots to quasi city parks to full on tourist spots. Dark tourism is nothing new as those of means in the 19th century visited asylums and other hospitals either to marvel as how culture was evolving to help those less fortunate or to gawk at those whose handicaps meant they were not welcomed (or able to function) in modern society. Sears doesn’t delve into the latter for obvious reasons besides it being out of the scope of the book.

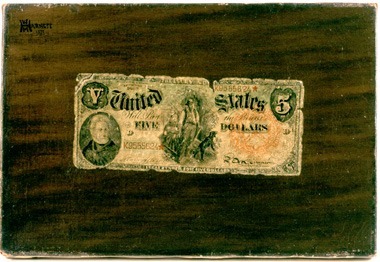

Moving back to the cities, Stephen Mihm’s A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalist, Con Men, and the Making of the United States takes a deeper look at those confidence men that I wrote about last week as well as the development of the American way of making money. The federal government abstained from its right to print and control money after the revolution which led to hundreds of states’ (and other) banks printing and circulating bank notes which were exchanged thoughout with the confidence that eventually they could be taken back to the source and exchanged for hard currency specie (gold or silver). There was never enough specie to cover all the legitimate bank notes much less any that were forged and counterfeited. In this sense counterfeit didn’t just mean fake bank notes, it could mean fake banks. Either way, it was the confidence behind the notes’ abilities to be traded for goods and services that drove the market, both the legitimate market and the counterfeit market.

The culture of counterfeiting emerged and evolved along with capitalism within the United States. Things were so bad in the 1830s and 40s that many people trusted (had more confidence in) bank notes from banks that didn’t exist or were illegal than they did in many notes from legal but insolvent states’ or municipal banks. It wasn’t just a matter of forging documents which needed handbooks to spot (many of which were in circulation in multiple editions), but catering to or on the confidence in the system. Interestingly Mihm ends the book looking at how the civil war solidified the federal government’s resolve to be in sole control of the nation’s currency through the development of the secret service to work to clear out the hard counterfeiters even as the nation’s confidence in their currency (and paper money) became an issue of national pride and confidence. In some respect the war and the post war economy made money a nationalistic issue. So much so that artist like William Harnett who was famous for illusionary paintings (trompe l’oeil) made to fool the eye, was arrested for his hyperrealistic paintings of money. Since his work was not created for the expressed purpose of passing them off as actual currency he was released and advised to stop.

I have always liked Harnett’s work. The hyperrealism paired with careful curation could lead people to thinking that the images were real. John Haberle’s Grandma’s Hearthstone composed of hunting gear and fireplace scene “even fooled the cat” who curled up next to the hearth to warm itself.

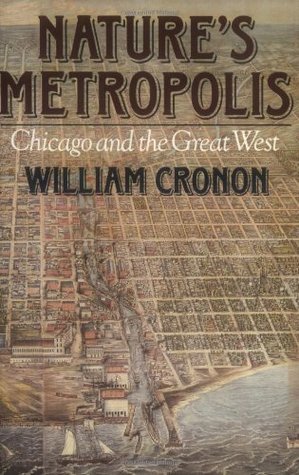

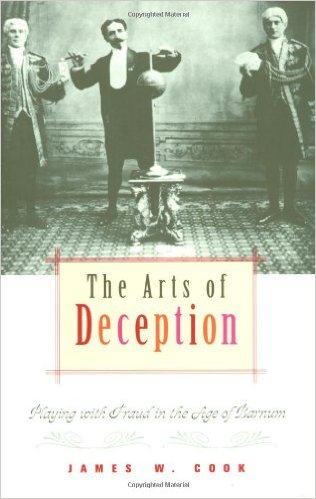

Harnett is also a great bridge into The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum by James Cook. There is an entire chapter on these tromp l’oeil paintings. In fact I don’t think I have ever seen the words trompe l’oeil in print as many times I have in this book.

These works are the hardest, realist evidence of the Barnum-esque deception that Cook describes in his book. The idea is that it was directed specifically at the emerging middle class who were in on the trick the whole time. Barnum mentions this himself in (one of) his autobiographies, that the public was aware of the deception even if they did not know how it was done, but the the entertainment was delivered at the full equivalency of the admission price. Two of the biggest themes in Cooks book is that this type of deceit is something that is part of all culture and returns from time to time without any real measurement cyclical regularity. The best 20th century trompe l’oiel painter is Wile. E. Coyote and his tunnels.

This ambiguity is part of the culture itself and is actually a way to understand and illustrate the same ambiguity that was 19th century American culture. While Cook ends with the tie-in with modern entertainment of scripted “reality” TV which, at 2001 was The Jerry Springer Show without it being mentioned, but would grow to the sufferable genre of popular television that is now going from Survivor and Big Brother to The Voice and Dancing with the Stars.

It isn’t all about paintings, slight of hand illusions are part of Cook’s analysis. One of the most interesting aspects is when a new magician takes he stage in New York only to have an Englishman in the audience go to the newspaper to reveal that he had seen these tricks when he as a child in England. Which brings to mind another of those period pieces that seem disconnected from historical fact on the surface, but, when you look more closely more parts of it are relevant than you would like to believe.

Cook also highlights professional wrestling as the best example of modern Barnum deception with the suspension of disbelief and the possibility of realism is served in equal parts. The audience is as much invested in the ruse as the marketer, and that is Barnum’s work and world in a nutshell.

Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show is similar in scope and arrangement as Reynolds Walt Whitman’s America that was part of an earlier set. Looking at it this way, you get the sense that they lived in different Americas. This might not be too far fetched given we are a nation of individuals as it is, and maybe there is historical precedent for that. It is also more Cook’s Arts of Deception in that Louis Warren outlines just how much the development of William Cody into Buffalo Bill was the marrying of fact and fancy from the earliest times through to Bill’s death. On the stage Buffalo Bill might as well have been Barnum Bill as he recreated the daring-dos on the range behind the footlights. The myth-building was exacerbated by the dime novels that were exploding into the hands of an emerging class of Americans who could afford books and have time to read them. Perhaps it was because of the inroads Barnum had made in culture that paved the way for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Those roads stretched from the western frontier across the Atlantic into the major cities of Europe (Cronon) who were just as detached from their own wilderness (Nash) as the Americans were from their cultural history (Sears). Throughout the interdisciplinary research one of the strongest statements in Warrens book is that the Wild West Show itself was more diverse than any city it ever visited. We also learn that Bill had an impact on Bram Stroker who was the agent for the most famous actor in England: Henry Irving. So much so that the Texas vampire hunter in Dracula is a remodeled character based on Buffalo Bill himself. The best way to sum up these books and lead into the problems addressed in the last one is Warren at length:

“Hailing from a West that was practically a borderland between real and fake, full of charlatans posing as heroes and of everyday people invited to assume heroic poses, [Buffalo Bill]…learned the allure of that tense space between authentic and copy, regeneration and degeneration” (543).

That copying, regenerating, and degenerating is nowhere stronger or more evident than the myths and stories that surround the battle of the Alamo. In Sleuthing the Alamo: Davy Crockett’s Last Stand and Many other Mysteries of the Texas Revolution James Crisps takes a long needed step back to figure out what we know about the Texas heroes and, more importantly, why we think we know it. I remember when the de la Peña’s journal came back to the front in the 1990s and revealed that Davy Crockett was executed after the battle. Growing up in Texas this was tantamount to high treason. Such is the devotion to the deception. How is it that Crockett is a Texas hero anyway, since he was only in San Antonio a few months before the battle? So much is his Buffalo Bill-esque celebrity that he overshadows all the Tejano involvement in shaping the Texas Republic. This is the large elephant in the room that Crisps little book points out. For years scholars have just been cleaning up after that elephant by rehashing old scholarship and not getting to the bottom of all the primary sources that don’t claim to be true, like some biographies. Crisps work with some of the most famous paintings of the battle reveal that in the 1870s early sketches varied greatly from the finished product after the turn of the century. These changed reflected changes in culture and racial tensions in Texas among other places in the nation. The book is written in a very personal manner which violates almost every tenant of academic writing, but is is important and useful as Crisp describes. His inclusion of a photograph of he, a cousin, and a black child was part of the impetus of the analysis. When a copy of the photo was finally found (a copy his cousin had) the third child, who was not family, but had lived as a tenant farming family under the cousin’s family, was cut out of the photo. This was very real evidence of what Crisp writes about in the text of Sleuthing. Two great things to take away from Crisp’s work are:

- The call to “Remember the Alamo” should be a scholarly charge

- “Even when it is ‘the other’ who is silenced, we lose a part of our history—a part of ourselves” (1980.