In the modern vernacular Richard Drayton’s 2000 book Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the ‘Improvement’ of the World falls somewhere between a “mic drop” and ” could’ve had a v8.” That is to say that his main argument that Britain was just as influenced by its colonial holdings as its colonies were by the crown is either an astonishing bombshell of historical argument or is the most obvious thing you have ever heard. As you follow his argument from the broadest coverage of colonialism down to the minutiae within the offices of Hooker and Gladstone in Kew and Parliament (respectively).

Tipping the scales at just under 350 pages, including nearly 75 pages of notes, this comes in as one of the most dense works read in this series. The work spans 500 years of history but these centuries are not divided equally throughout the text. The bulk of the work looks at what historians call the “Long 19th Century” which spans from the French Revolution to The Great War (World War I). This section covers much of the same ground as the previous accounts on the Kew Gardens and Hooker’s network of collectors. What it adds is more interaction between Hooker and politics which he had little or no control over. If we compare it to the previous book on Hooker we have people like Gladstone treating Hooker in much the same way he was treating his underling collectors Colenso and Gunn. (If that does not ring a bell, see the post “Imperial Nature“).

India, the jewel in Queen Victoria’s crown, shows up with some real heft in the latter portion of the book and it would be a useful addition to any seminar on Indian history even removed from the broader narrative of nature, botany, and Kew (which, incidentally is really impossible to do once Drayton reveals how important they all were to each other). That this book is not part and parcel of every general Victorian England course since its publication in 2000 is a bit of a missed opportunity. While it is not a book one would casually pick up at Barnes and Noble, it is both readable to a general interest audience and in depth enough to be used as a textbook.

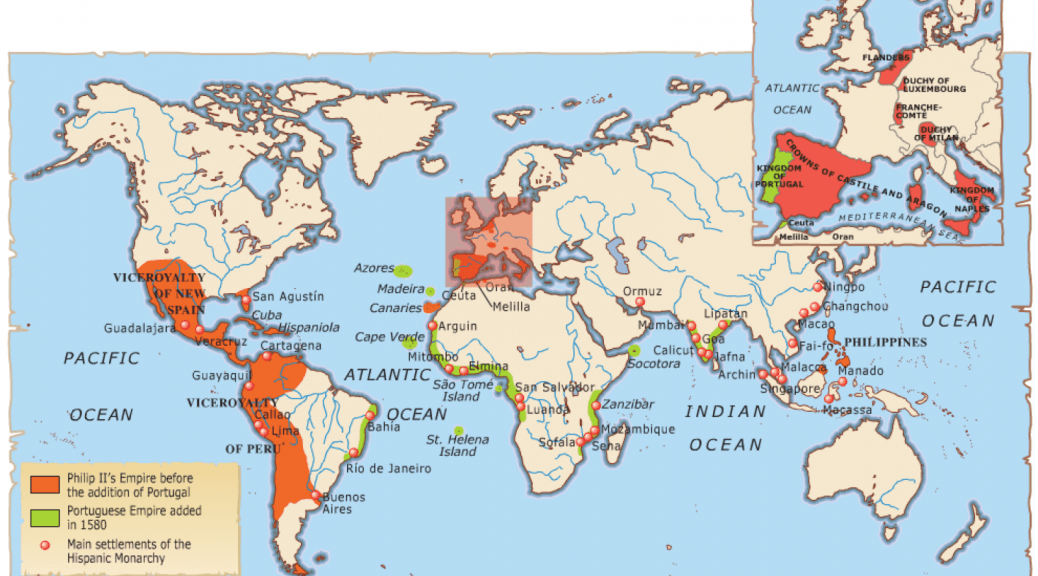

Drayton also provide a large canvas to analyze what the subtitle called the ‘improvement’ of the world. Like many of the Renaissance paintings (if we are to stay with the painting analogy) Drayton’s canvas is painted on both sides. The most obvious, and most displayed side, is the general unidirectional history of how Britain conquered the the world, brought in multitudes of land, culture, and innumerable people under the crown, and how the sun never set on the British Empire without asking permission first. It is when Drayton’s canvas is flipped that the reader is given a view of the influence that flowed back upstream and into the head of the largest landowning government in the world. That powerhouses of trade and politics in London were (and could be) influenced, however indirectly, is exactly that point which makes this book either breathtakingly important or glaringly obvious.

The importance that agriculture (specifically botany and forestry in the case of Drayton’s smaller argument) played on the establishment and continued success of such an empire is also something knew for readers who are only family with England as a “nation of shopkeepers.” He even admits in the preface that another subtitle might have been “The agrarian origins of the British Empire” (xvii). As someone who grew up on a farm in the middle of the Big Thicket of Southeast Texas and was active in the Future Farmers of America (FFA)–including Forestry–in high school this seems like a more obvious direction of inquiry than not. Even one of the most popular authors of the 19th century was involved in agricultural reform all across the British Empire. H.Rider Haggard was sent to South Africa to work of the governor, and through a series of reappointments managed to be on hand when the British annexed the Transvaal. While not evident in his adventure novels, British colonial agricultural practices were an enormous part of Haggard’s life.

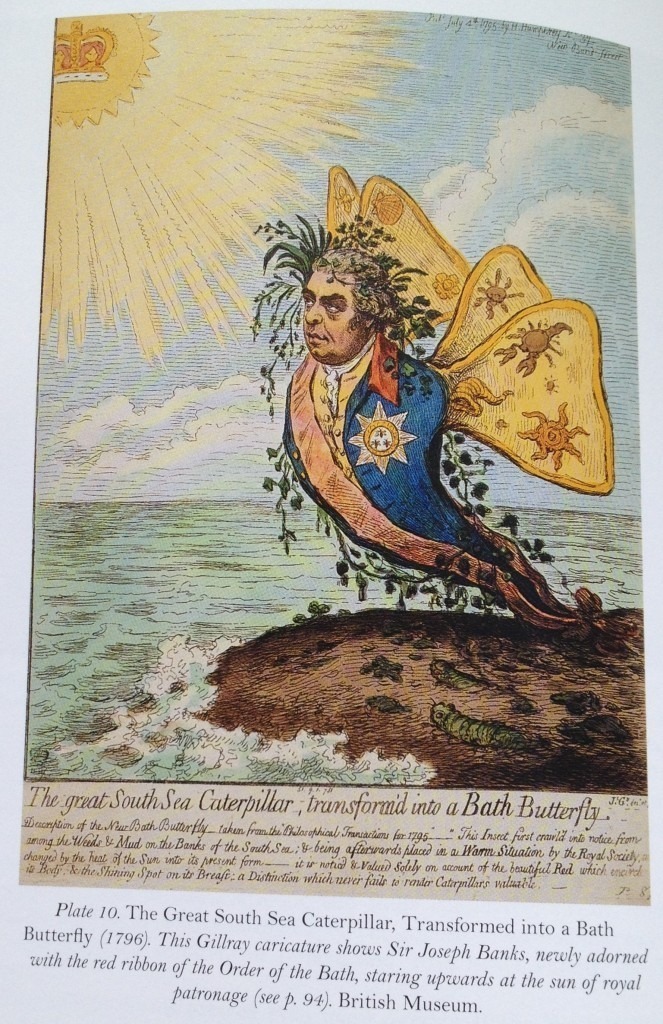

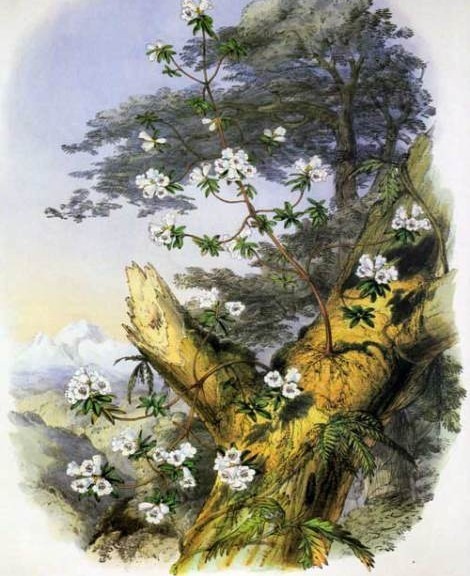

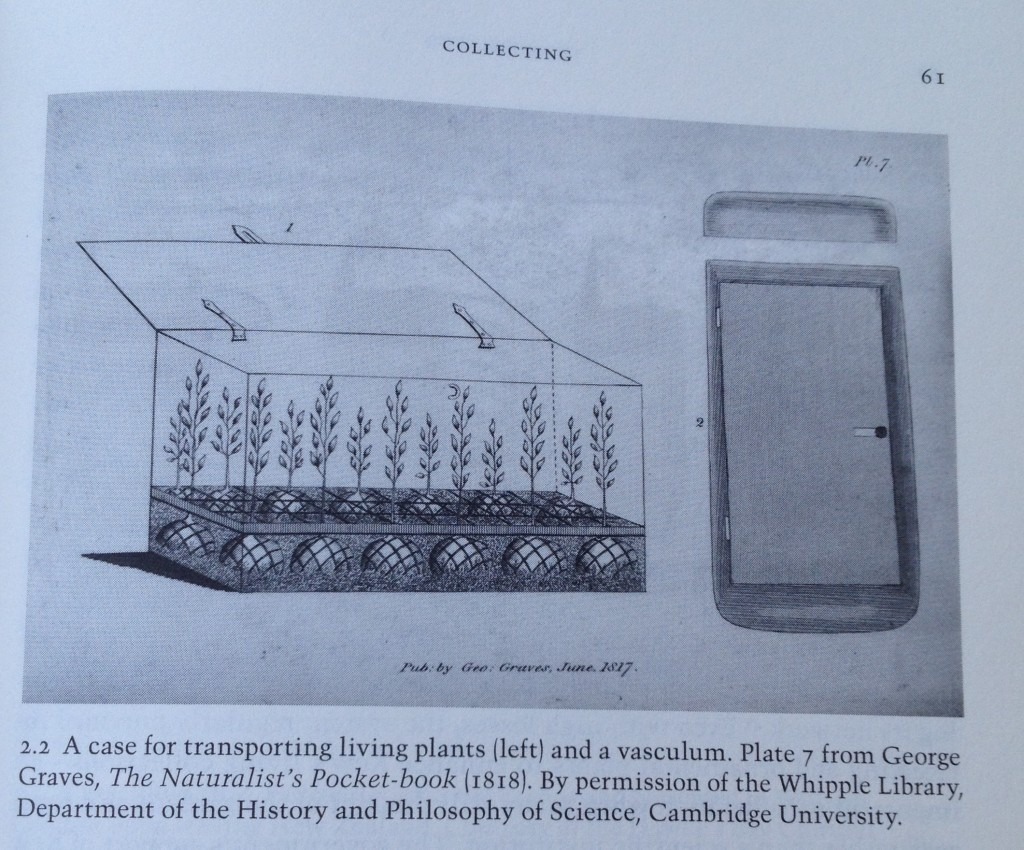

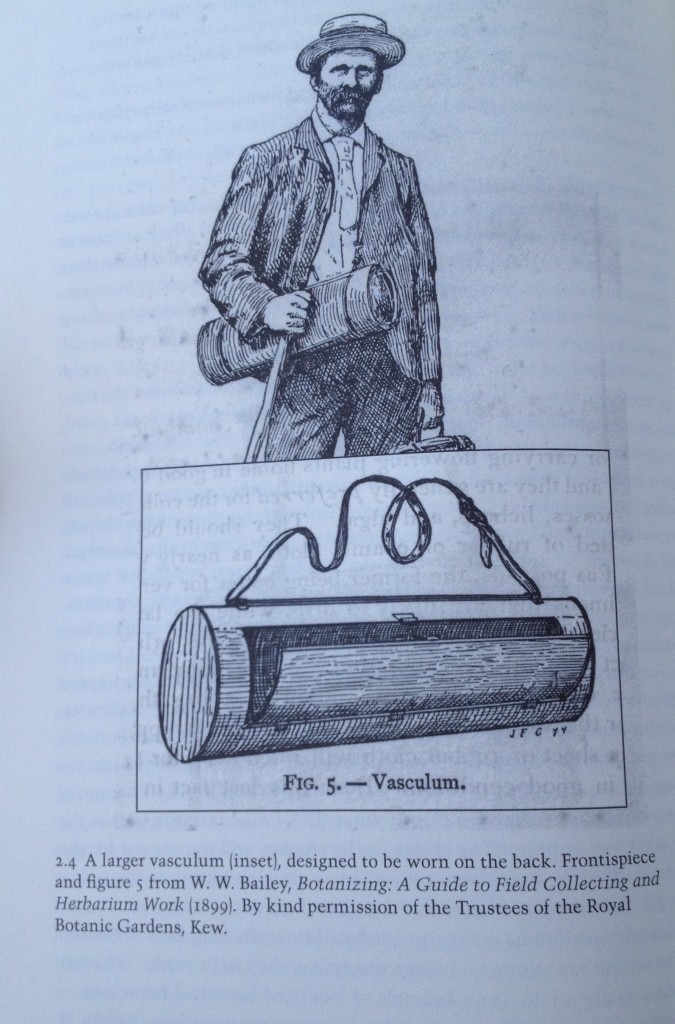

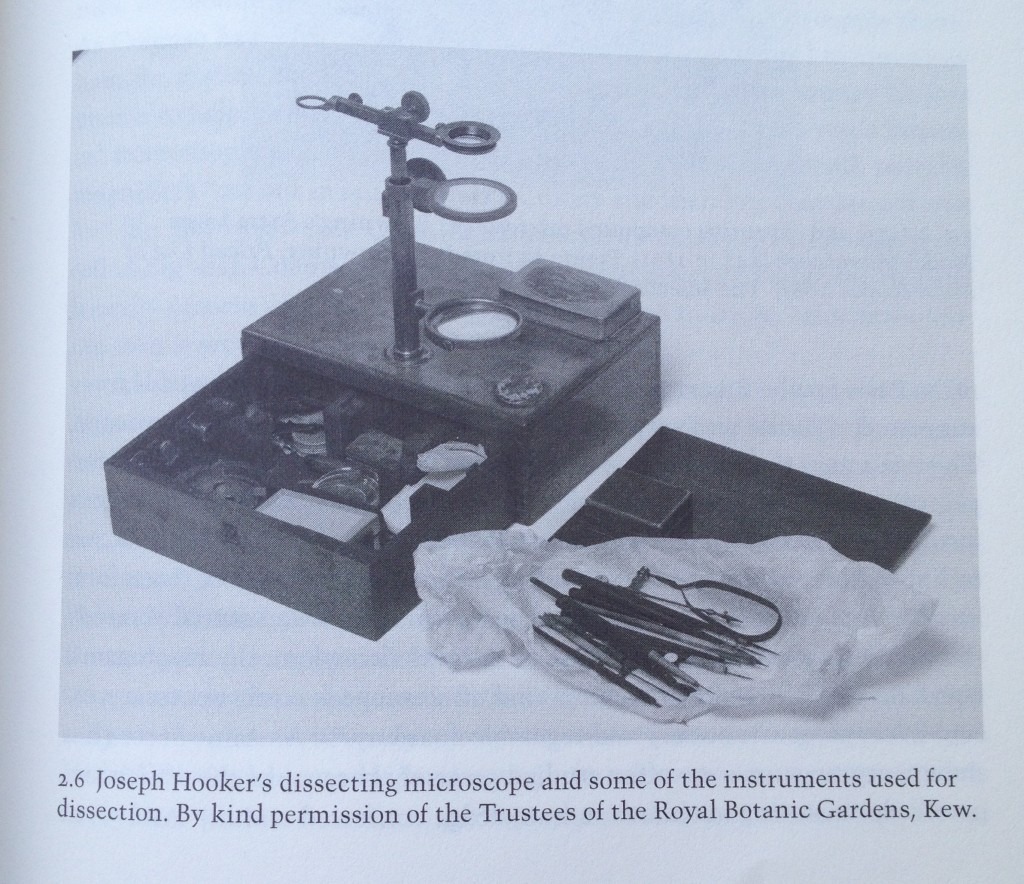

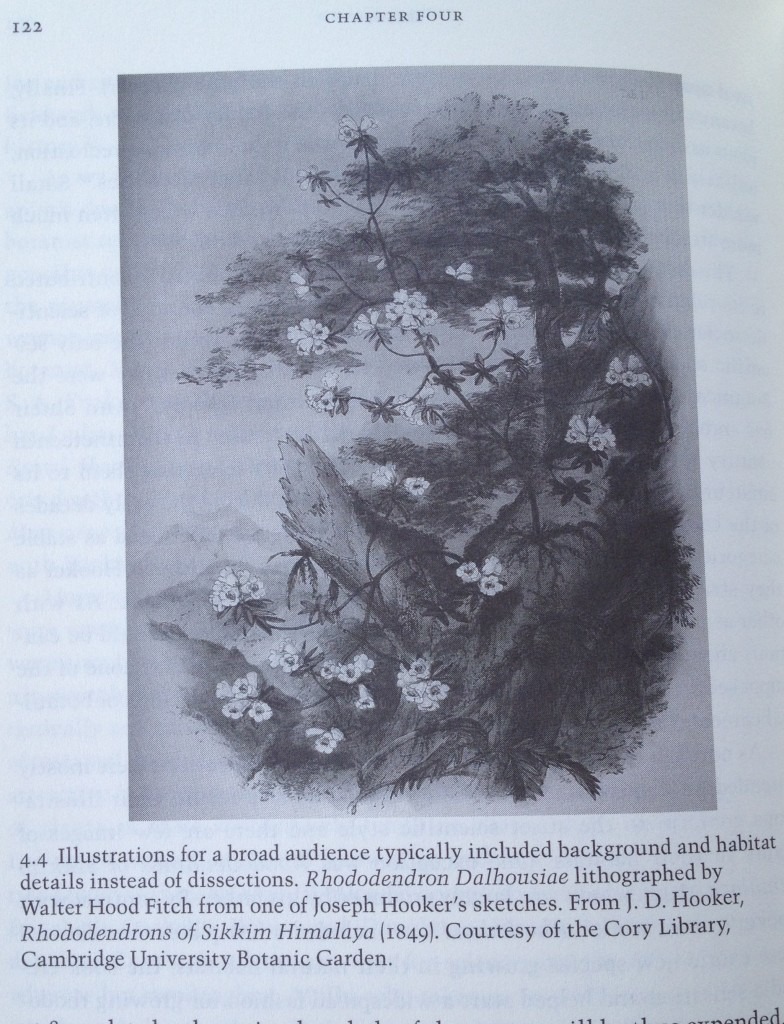

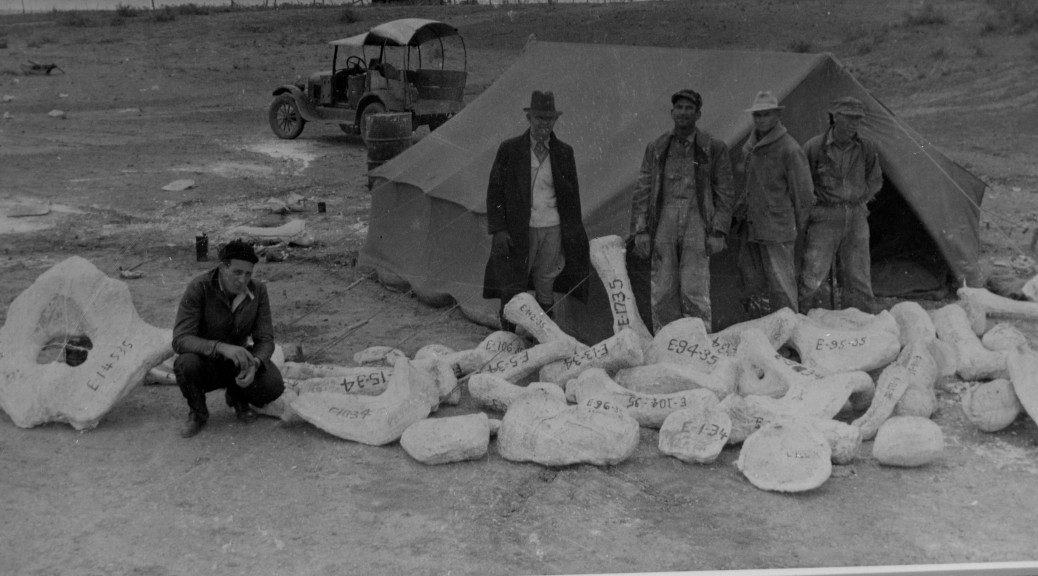

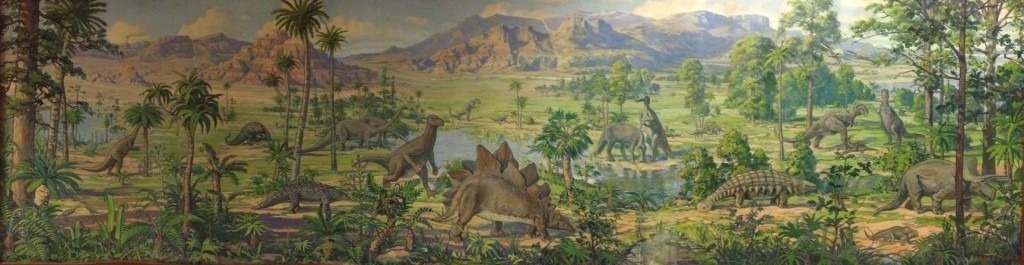

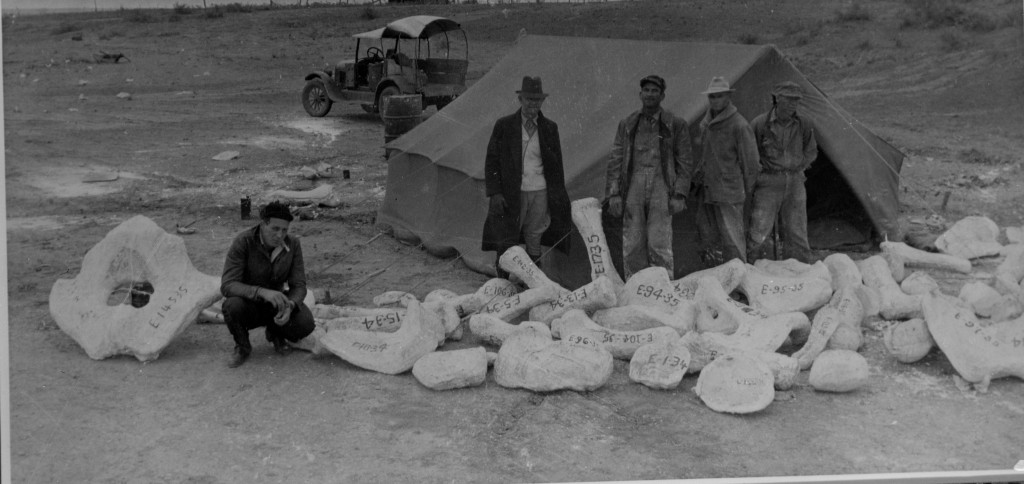

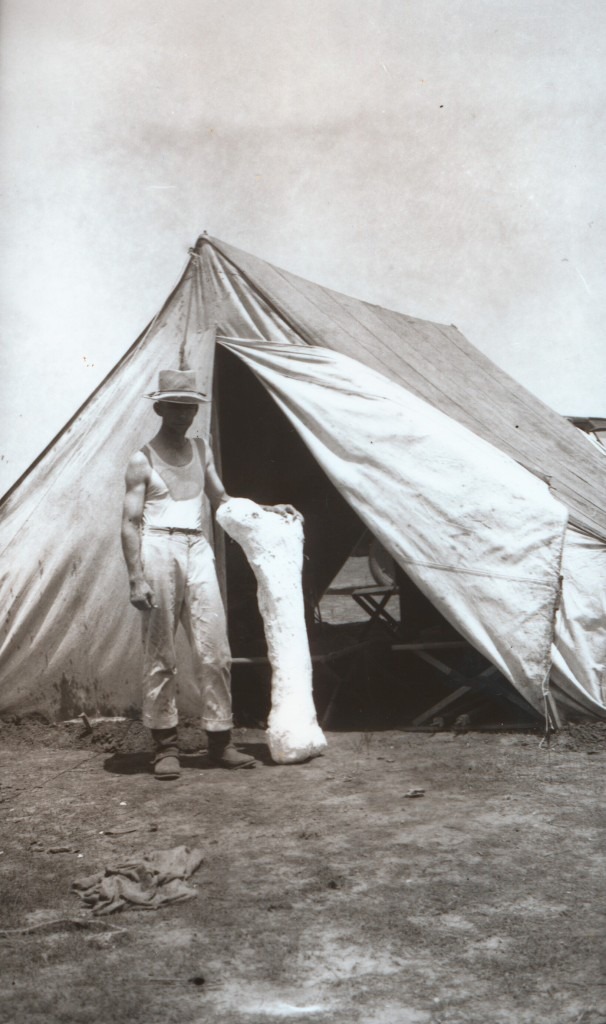

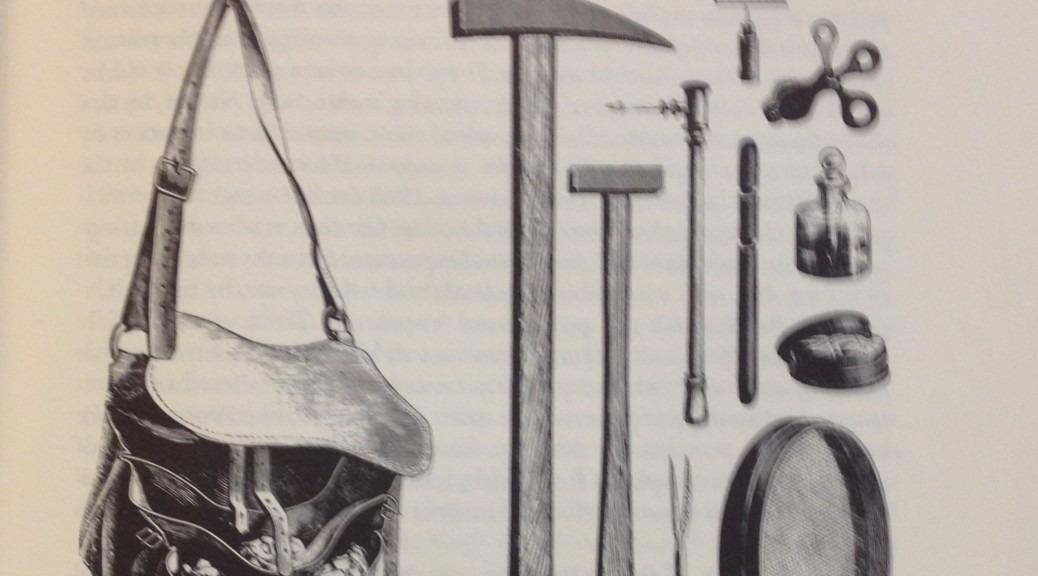

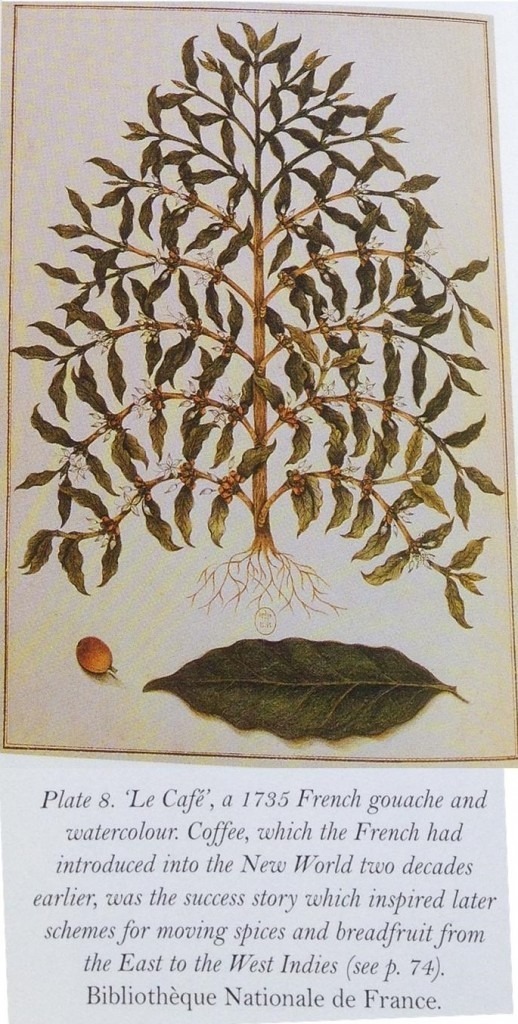

The book is lavishly illustrated–even with color plates!–for a university press. Colored plates, maps, and photographs are not random choices, but each further the argument that Drayton structures throughout the text. The chosen illustrations go well beyond the standard portraits of the Joseph’s (Banks and Hooker) in move into very helpful visual analysis additions to the text. It is little wonder that the math through the preface work out Drayton’s labors to around a 15 year endeavor. My favorite image for image sake is Joseph Banks as a Bath Butterfly. My choice for the image that warrants having another book written about it is an image connected with Hooker’s “absentee master” status at Kew. Drayton reveals that it was all Hooker’s traveling abroad, taxonomy work at home, and presidency of the Royal Society that allowed William Thistelton-Dyer to work as the de facto director of Kew even before Hooker officially retired. The photograph shows Joseph Hooker on a collecting trip to, of all exotic places available in 1875, the American West. Since a third of my comps are overseen by a professor of art and art history of that same American West, I was excited to see this connection. Especially given that my original connection to even visiting the University of Oklahoma came under the guise that I would be studying Victorian Science (and under the very person that I am working through this reading list with). While 1875 is a bit late to be looking at the U.S. as a colony, it does reveal Imperial Science knows no geographic, political, or temporal bounds.

If there is no other example of Drayton’s argument within the book, the very existence of this work would do well as an object lesson for his philosophy. “Richard Drayton was boen in the Caribbean and educated at Harvard, Oxford, and Yale. A former fellow of St. Catharine’s College Cambridge, and Lincoln College, Oxford. he is currently (2000) Associate Professor at the University of Virginia” (from the back duskjacket). On top of the back and forth of the author through the academy, the book was published by Yale University Press’ London office.