I have found it odd that the case has to be made to study photography and art as source material and not merely “visual aids.” The only think that is even more odd is that this case is relatively recent.

The four books and one article in this little operating section tend to all say the same thing–photographs are important not because they are photographs, and not even because the subjects of the photographs, but because they represent a distinct moment in time of an ever-changing culture. The contextual culture of regional and temporal data are frozen in time just as the faces of early portraits. Each work provides its own examples of why this is an important shift in thinking about images. As Martha Sandweiss points out in Print the Legend sometimes what isn’t photographed or what was photographed and then lost can reveal as much (if not more) about a certain moment in the past. Sandweiss provides a solid foundation that scholars should use in reassessing their relationships with photographs. I believe this improved methodology will also easily cover other visual culture as well. Print the Legend could easily be a history of technology work as it follows the exponential developments of photography across two generations (her investigation ends in the 1890s) which happens to parallel the development of America’s mythos regarding their newly acquired and explored territories. For my purposes, she provides the best answer for why, after a MA in American History I have shifted over to work with the Art Historians for my dissertation:

“A lingering bias in historical training teaches would-be historians to value the literary over the visual or material, and teaches them how to query, challenge, and interpret literary documents, while leaving them few analytical skills for the interpretation of visual records”

While looking back through some of the little work I have done with photography (only really starting in 2014) I did find a C-SPAN video of this very book, and it is worth the time you can devote to it:

A funny aside is that you can purchase this as a DVD or an MP3. The latter of which you can listen to Sandweiss describe the photographs, which leads one to believe they missed the point.

Alan Trachtenberg’s Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evens is one of the earliest books (1990) to call for a shift in the understanding of photographs. It is one of those books that requires complete attention and an appropriate amount of pyschological working up to undertake. It is dense.

Not in a bad way, but at times the theoretical asides (which I am certain Trachtenberg does not see as asides) get in the way of the point he wishes to drive home. My first run in with Trachtenberg was his first book about the Brooklyn Bridge. While reading this I went back and thumbed through some things in it on a hunch. Photographs does continue Trachtenberg’s thread of America as imagination. In fact in 1965 he called it “An America of the imagination.” In addition to starting the stone rolling on photography reassessment in history, Trachtenberg offers a short sentence that I am certain will come up for expansion in my future work:

“Thus O’Sullivan placed the survey camera among the instruments of practical science, allowing the history and meaning of the Western surveys (the conjunction of “pure” science and imperial economic enterprise) to reveal their contradictions” (289)

The remaining books in this section could be considered “popular” books each focusing on a single photographer as they managed to work their way through the new continental nation and new technologies in order to make names for themselves as photographers.

In Meaningful Places: Landscape Photographers in the Nineteenth Century American West, Rachel McLean Sailer highlights that print making and mythmaking went hand in hand. Few of the landscapes are void of human life or activity, to the contrary many settlers used photographs of themselves in their new spaces as vindication for the success and progress of American culture. Photographs provided constant reassurance that people were indeed where they belonged. A sense of place for people who had left their cities or even countries in the case of foreign born immigrants was something that most settlers struggled to maintain, but photography, according to Sailer was instrumental in calming some of those unspoken fears.

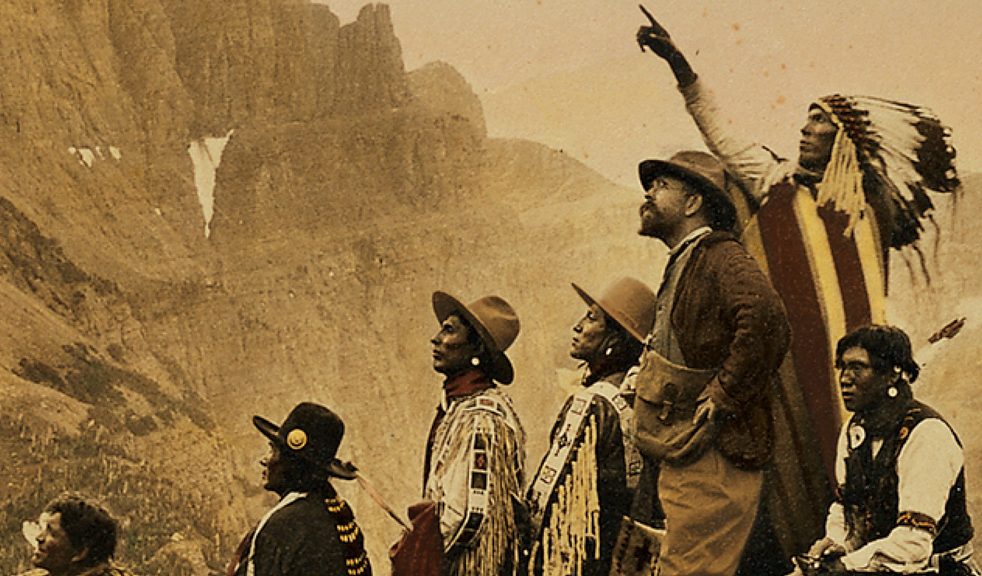

Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis is another notch on Timothy Egan’s literary gun. I have personally read two other of his works: The Worst Hard Time and The Big Burn. Egan doesn’t write books you can glean which is one of the reasons I enjoy assigning them. The book itself follows the drama of Curtis’ life as he moved across the West capturing moments that were fading away. The story of forgotten photographs rediscovered are as much the legend as Curtis’ “quixotic” quest to capture native life. Which I think is captured better in this variant cover:

The renaissance of his work in the 1970s installed Curtis at the forefront of historical photography. Even as historians in the 80s attacked his work for being staged or “playing dress up.” Egan points out that Curtis heard these attacks during his life, and never denied it. His defense provides insight into his work and the importance of photography in the late 19th century: he wanted to represent the past, not document the present of the future. His time in Oklahoma in the 1920s saw many of the natives already fully remodeled into Euro-American culture and his pace in his “race against time” hastened. For Curtis himself, the 2001 documentary Coming to Light is an excellent way to start. I apologize for the ads in the linked video but it was the only site that had the full program to share. Here is a snippet. You can see the whole thing here.

Curtis was involved in the Harriman Expedition in 1899 which, at this planning stage, will be the final expedition in my dissertation. Curtis also employed the new technology of moving pictures after the turn of the century, which ties back into the final book of Eadward Muybridge.

As with Sandweiss and others, the nature of photography in the American West also serves as a history of technology. Nowhere in these readings (maybe even more broadly) is that more evident than in Rebecca Solnit’s River of Shadows: Eadward Muybridge and teh the Technological Wild West. In fact, Muybridge’s life can be seen as a parallel with both the arc of the West and the rise of photography. He “invented” himself in western culture, photographed through the landscapes as did his contemporaries, and then made studies with the movement displayed in still photographs. His moving pictures were the legacy his family life never produced. Solnit describes Muybridge as a man who “split the second,” which had “as dramatic and far reaching [effect] as splitting the atom” (7). One reviewer did not care for this phrasing, but given the circumstances and the tenor of the book (and Muybridge’s life) I think it fits.

The final piece was an article in the Art Bulletin in December 2003 highlighting Timothy O’Sullivan as a survey photographer. Trachtenberg mentioned O’Sullivan in the quote above as the person who brought photography into the came of scientific instruments. Robin E. Kelsey’s article “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74” look at the photographs as a new form of graphic representation. That is a more precise way of expressing the landscapes, forms, materials, etc that the survey encountered. “Pictorial Rhetoric” became the tool for people like Ferdinand Hayden in order to increase (or sustain) federal appropriations for their continued surveys. One of the mor interesting portions of the articles many photographs is the sort of “line of custody” we see in O’Sullivan’s (i.e. The Survey’s) photographs:

A final thought on this reframing of photography as primary sources is stirred by the author byline in Kelsey’s article. “He is preparing a book on Survey photography.” If the article is any indication it will be an excellent book. I wonder though, if the pendulum is swinging too far into the study of photographs as primary sources that they will become more detached from their created context as they become topics or study. Something like Survey photographs is an excellent topic to undertake, but at the time the photographs, as graphic representations, were another means of transferring information and raising interest in the surveys, government exploration, and the American West as construed by the myth-makers. I think it shows the power of photographs to evoke audience interest and emotion that no popular book has been written on the Survey graph or map making or their field reports as entities. Journals have been reprinted and photos as well, but I think it will a long time before the similarities and differences between visual and literary will ever be hammered out.