David Elliston Allen’s 1976 social history of the naturalist in Britain is by all accounts “a classic.” Interestingly enough it was republished in 1994 by Princeton University Press from its original Penguin Books which brings into the question the relationship of popular press vs rigorous (inflated pricing) of university presses, but you can take that up on your own.

This is a delightful foray into the beginnings of naturalist thinking, organization, grouping, discourse, or just about any other adjective you can use to describe natural history in Britain from late 17th/early 18th centuries right on through to the 1950s. That alone makes this a great survey into one nation’s establishment of a “scientific discipline” for the lack of a better phrase.

It is hard to make precise points about Allen’s book because it is so broad in scope–both temporally and by topic. Being a historian of geology (paleontology and earth history, etc) my favorite was Chapter 3 “Wonders of the Past” that is a less than 20 page foray into the shaping of our relationship to spaceship earth.

Other chapters are similar chunks of larger histories such as taxonomy, the amateur club, the victorian world (very generally), and the rise and fall of the structures of natural history. Social history has moved well beyond what it was in the mid 1970s and if you were to present your committee with an outline using the chapters of this book you would be asked to pick one of them and get back to them. The very thing that makes it an excellent source to teach a survey of natural history (in Britain, remember) is what makes it a bit chuff for super deep prospecting.

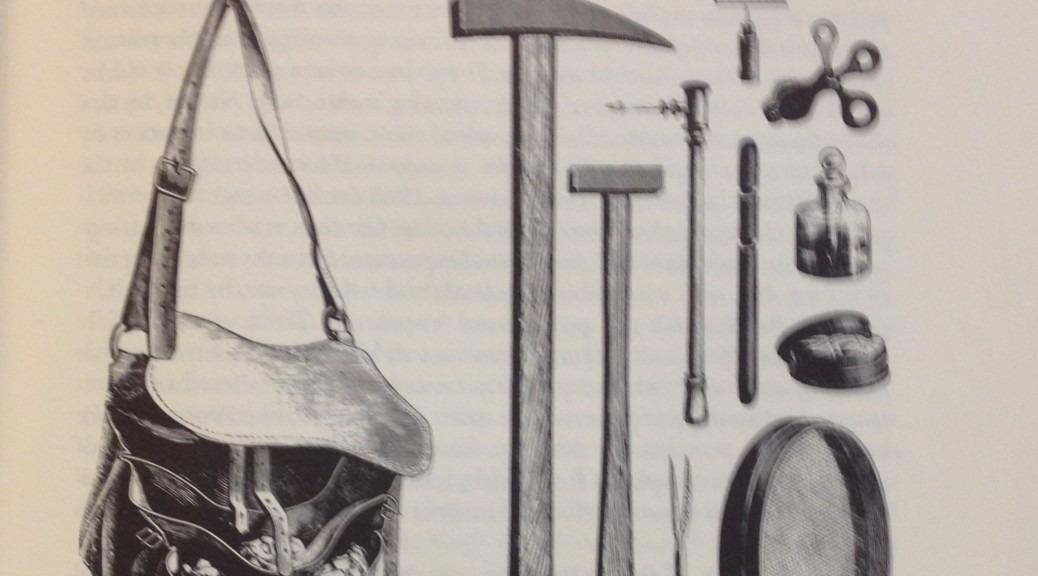

The illustrations alone are worth having this at hand in the library. Even in the austere black and white (as most of these are woodcuts, political cartoons, or black and white photographs) they provide a larger piece of the narrative of popular culture and public involvement with natural history that sometimes falls flat in the laundry list of organizations, field clubs, and/or publications (including photography later).

Allen touches upon a phenomenon that is of great interest to me, and is becoming more of an issue today (especially in paleontology) the relationship between the amateur and the professional. This is something I explored in my thesis The Gilded Skull in England’s Closet which centered on the Piltdown case and the involvement (and voice) amateur collectors and antiquarians had within the burgeoning scientific circles and societies. Now I know by 1908 the Royal Society was hardly an upstart organization, but it had had its share of issues along the way and a hard arm of natural history within the society was closer to egg than to hen.

What can amateurs contribute to this new professional science? That all depends on how these amateurs are trained, how they collected these natural history specimens, and a host of other issues at hand. That is the ever present thorn in the side of vertebrate paleontology presently, highlighted no better than with the Sue debacle and the more recent “documentary” providing great detail on the David against the Goliath government for control over fossils which have a high market value. (I am speaking of Dinosaur 13, and it was pitched exactly as a David vs Goliath tale).

Allen’s studies on the intertwined and ever-changing relationship between those on the inside and those armchair naturalists (splitting and reforming, and looking at membership lists) provide an insight into the world between the chasm between the working collector and the scientific collector. The modern problem, aside form market value, is something that Allen’s work reveals was not a problem in the late 19th and early 20th century–the careful logging of provenance of specimens. The field clubs and societies were extremely careful in how they trained their members and noting where all their specimens were collected. It was a singular lifetime hobby for many of the members, not one of 4,973 things to fill the schedule of today’s weekend warriors.

These are generalizations, but they are not overarchingly so. The change in market value of specimens during the time that Allen’s subjects were working until now is evident. Natural collecting, when done by men (and some women) of means is a pursuit of knowledge (maybe fame if something could be named after them). Some made money from selling their specimen but few made a living doing so. In fact, few needed to make a living at all. So they came with a personal vested interest of name and reputation behind it. Not quite so today.

I had the good fortune to spend some time with Dr. Time Rowe from the University of Texas the past two days. He was in giving a lecture on fakes and forgeries in vertebrate paleontology so we talked a lot about motive, resources, and the need for regulation. Anyone can track market values of fossils on eBay or at gem and mineral shows that there is a market value for these things outside of science is damaging the science. There are many examples of forgeries undertaken for a multitude of reasons, but the influx of fakes, some very good, and some very Piltdown-esque stem from the fact that slabs from China revealing a creature with a full 50/50 layout of avian and dinosaurian features can carry a price tag of $80,000.

What has replaced due diligence in collecting bugs, birds, beetles, plants, fossils –highlighted in all of Allen’s chapters– is a receipt and (if you are lucky) a “certificate of authenticity.” The bottom line here is really there is nothing new under the sun, and human nature is much more similar (and hard to explain) throughout time than we sometimes image (or like to think about). If you are teaching a survey of natural history course Allen’s book will be useful for a variety of reasons not least because of its easy to digest chapters and huge scope (even though it is confined to Britain), but also pragmatic reasons of cost for the students. You may also be able to open a dialogue about the second reprinting 20 years after the first, but no third edition in 2014. It also provides a good example of early work in social history when it wasn’t quite as part of the historical canon as it is now.