Can a book only 11 years old be a classic? If any work can claim to be such it is surely Fa-ti Fan’s British Naturalists in Qing China: Science, Empire, and Cultural Encounter. This is a huge geographic and political shift from the previous books that have dealt with India and British India. I make that point because it is important to remember that the earliest relationships with China were undertaken pretty much under Chinese terms. Even following the end of the Opium Wars and the forceful opening of trading ports China was never a colony under the British Crown.

Can a book only 11 years old be a classic? If any work can claim to be such it is surely Fa-ti Fan’s British Naturalists in Qing China: Science, Empire, and Cultural Encounter. This is a huge geographic and political shift from the previous books that have dealt with India and British India. I make that point because it is important to remember that the earliest relationships with China were undertaken pretty much under Chinese terms. Even following the end of the Opium Wars and the forceful opening of trading ports China was never a colony under the British Crown.

That is something that is easy to overlook within all the accounts of British fieldwork is lumped together into the standard imperial-vernacular polemic. Maybe polemic is too strong a word. Either way it is the standard narrative of the boundary lands–theoretical as well as physical. In less than 200 pages Fan is able to reveal that is much more than what meets the scholars eye, and that much more is needed to understand the nuance, and highly independent (and interdependent) relationship between those that knew the raw material and those that wished to classify it.

Fan’s methodological approach to including the knowledge of the Chinese everyman into the larger scope of Imperial Botany and the powers at Kew should provide anyone researching fieldwork in any region with a more than adequate framework with which to present a fully nuanced and historical account.

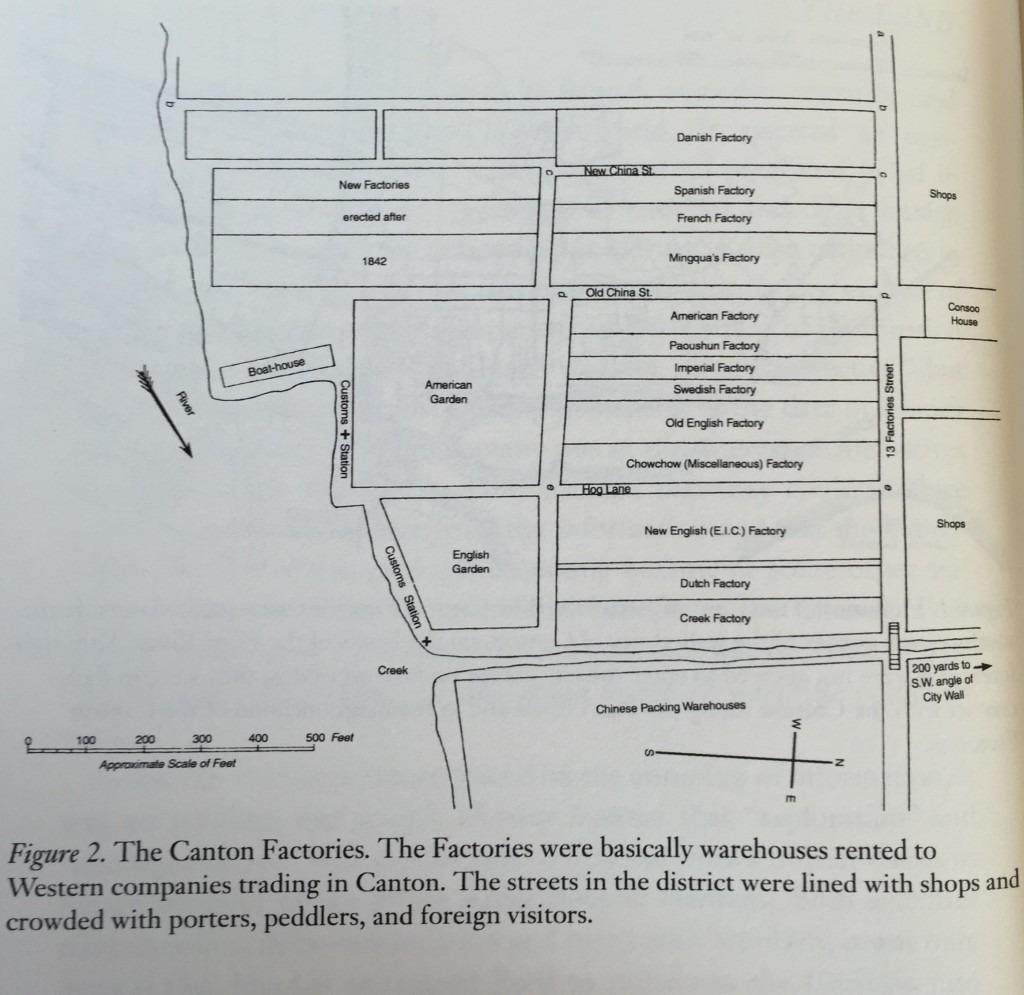

He deftly begins with the standard setup presented in historical sources of how Britain was setup in Canton in a line of warehouses and were forbidden to enter the city proper. It is when he looks deeper into the relationship between diplomat and merchant, trade consul-man and informant, outsider and local, that his research provides both a broad view of natural knowledge and a focus on the actual objects and information being traded.

One of the joys of the book is the attention that Fan pays to the folklore and literary influence that existed during the early 19th century Chinese natural history. Throughout the book he shows just how intertwined natural history and sinology was during the period. One had to understand the nature of the Chinese culture before they could understand the nature of China.

One of the largest differences that face the standard explorative travel adventures was that China was no “Dark Continent,” or unexplored rainforest. China had an infrastructure that lent itself to travel in ways Dr. Livingstone could only have dreamed about. Once Kew (and other collectors) had established their network in Canton, and eventually other locations, those naturalists on the ground set up networks of their own. Sometimes they had to create a network from scratch, but this was rare due to the expansive success of the French missionaries that had been in China for much longer than British naturalists.

Many of the Chinese natives that provided local knowledge, translations, and information to the naturalists were Catholic converts. The “imperial model,” while still employed by many of the British travelers in China, carried much less authority. In fact, outside of British controlled trade ports it carried nothing. Armed with their own superiority, many found themselves relying on the Chinese more than they cared to admit. It is also a delight to see just how much the naturalists relied on the knowledge and skill in collecting among the rural Chinese farmers and hunters in order to fulfill their orders and fill their collections.

My favorite story within the book is actually a really good case study into the operations of British natural history in China, and it was undertaken by a Frenchman. Albert A. Fauvel was a member of the Chinese Customs and as such worked closely with the British. In charge of the Natural History Museum in Shanghai Fauvel’s interest in the natural history of China was far more than a hobby. It was Fauvel who first published description of alligators in China.

Fan’s analysis of Fauvel’s article is the perfect way to understand how necessary it was for naturalists in China to also be involved in the study of China itself. Fauvel traced the descriptions of the Chinese character tuo to disprove it referenced either an iguana or a lizard. Following descriptions of tuo wherever he could, he surmised that the land dragon with medicinal meat and skin good for drums was indeed an alligator, not unlike those described by John James Audubon and others working in Mississippi and Guyana.

What set Fauvel apart was not his mere description of the Alligator sinensis. Fauvel took the time to understand where the alligator fit into Chinese mythology, legends, and folklore. In China, Fauvel worked from Chinese text to understand the alligator in theory, but was unable to establish it as a new species without specimens. From the specimens in China he was able to work backwards–comparing the Chinese specimens to images in taxonomic reference books. Here we see an almost perfect mirroring of practice in the field involving both text and object.

For my own interests into account, even those beyond the study of field work, is the early discussions of paleontology with China. Early geology in China was limited even more than the other field sciences. One of the brief asides (which will lead me in search of the reference) was the mention of William Frederick Mayers working with Chinese text (in the same manner as Fauvel) to understand China’s prehistoric life. Without any physical remains or specimens to collect, Mayers was forced to work exclusively with Chinese literature, folklore and myth to find “descriptions and drawings of a huge, hairy, rat-like creature living underground, which he believed to be a mammoth” (118).

Modern paleontology is making up for lost time on the China front. Just during the few days I was reading this book, dinosaur eggs found by workers building a road and the discovery of a bizarre leathery winged dinosaur were announced. Some things have not changed however, as any spectacular, too-good-to-be-true discovery is announced, it is received with some skepticism. This isn’t exactly the same mistrust that 18th century naturalist had of unobservant Chinese, or those who did not bother to separate fact from fable. There have been some high quality fakes coming out on the black market of China, and in the case of fossils in the 21st century just as many are made in China as found in China.

I try to always balance out everything I read with something that I wish had been included or different about the book. With this book it was more difficult for content, but easy to be petty. It is an oft repeated lament of mine about color images and illustrations. There are a host of reasons that black and white and greyscale are the case–ultimately I would say would be the cost of the final result being restrictive to its intended audience. However in this case the beautiful description of the illustration of the betel palm that included fruit that is in varying stages of ripeness along with the cross sections of the fruit, a full leaf and the entire tree would have been nice to see in the detail with which Fan describes it.