There is no survivor, there is no future, there is no life to be recreated in this form again. We are looking upon the uttermost finality which can be written, glimpsing the darkness which will not know another ray of light. We are in touch with the reality of extinction.

— Henry B. Hough, Domesday Book

The largest part of being a graduate student is writing. Many times you take the same class as 15 undergraduates. What sets you apart from them is usually an extra paper. If you are lucky you get to do a research paper. If you are me you get to write a historiography. I will go on a tangent here briefly about why I hate these things and find them a complete waste of time. As a finished product, historiographies are hyped up literature reviews. They are a collection of summaries of works done on a topic. You (or me in this case) have to try and go beyond the original authors interpretations, and form your own.

Maybe it is because I have really only written historiographies on topics that I know relatively little about that I cannot seem to make that leap into forming my own. I could have formed many more interpretations had I been given clearance to research a topic thoroughly and not just look at how other people looked at it before. I think they are bunk, and unless I have to write one I will not. But, I have to.

The trick to graduate school is to use all these extra papers to build towards your thesis. I am working on wild animal collecting for the Nation Zoo in D.C. in the early 20th century, so I theoretically, I would try and pick topics that would allow me to run towards that. I sort of have one for the circus paper, but I will talk about that one later.

The reality is most of the time you cannot. I took a seminar course over the holocaust course last semester and wrote (a lot) over something that has nothing to do with animals, zoos, museums, or any of the other scores of interests that I have. I learned about source material and memoirs versus history approaches to things, so I do not chalk it a total loss.

So getting to take a course over the British Empire should offer loads of things to study. Oh, how it would if I did not have to write another stupid historiography. Sources, and hopefully contradicting or argumentative sources are the key. So trudging through the library that I live in I came up with things that happened during the reign of the Crown.

I could write on the Piltdown Man, the Cardiff Giant hoax, Alfred Wallace and Darwin’s co-discovery, or any other number of things. Great topics for research seldom make great topics of historiography. So I chose something sort of related to animals, and now I have to, in some form or fashion, collect it into a coherent work in a manner that I disdain.

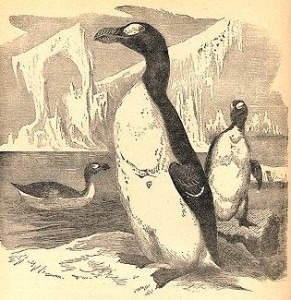

Enough whining about that though, the thing that has piqued my interest is extinction. For the purposes of this paper I will look at extinctions within the empire. Specifically I will look at two. One from South Africa, another from Australia. The passenger pigeon does not count for this. I will also add one that was ‘discovered’ relatively recently for a large mammal.

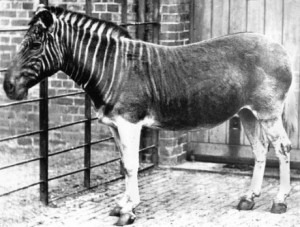

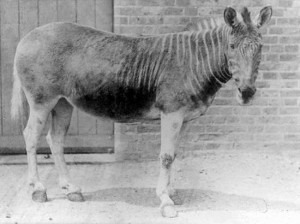

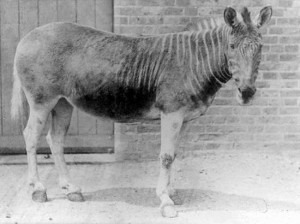

First, the Quagga, this is the sand colored horse with the zebra striped head. The last one died in an Amsterdam zoo in 1883.

|

All accounts I can find say her name was Jane.

|

The short story for the Quagga is that there was always a contention among scientist as to whether or not they were a distinct species of zebra or a subspecies. Most likely the last wild Quagga was killed in the 1870s. The creature had disappeared before they could determine if it was a separate species or not. However, the Quagga was the first extinct organism to have its DNA studied and researchers at the Smithsonian Institution discovered that it was not a new species but simple a special variant of the regular plains zebra.

The Quagga Project began selectively breeding plains zebra in 1987. As of 2004, through fits, starts, and relocation there are over 80 zebra in nearly a dozen localities around Cape Town. This whole study brings up another argument over the difference in subspecies and what we would call “breeds”. Below is a VofA news report of the Quagga Project.

The problem that I foresee with this is not one of science, but of perception. As mentioned in the video, this must not give people that feeling that it is okay if something goes extinct now, we can just recreate it in a lab somewhere. While that is amazing that we can do that, it is ecologically a moot point. That way of thinking is prevalent in today’s youth and public. We live with a “fix-it later” mentality. For some species there is no later.

Once these animals are gone, there can be attempts made by brilliant people to restore what they can, but they are extinct. That word, like so many others, has been thrown around and attributed to so many things that the depth and reality of what is means to be extinct is sadly gone.

There are two people I always think about when I study the Quagga, one is the hunter in South Africa that killed the last remaining one in the wild. What did he think, how did he feel? Don’t get me wrong, I am a hunter. I am not trying to ban hunting, but did he know there were fewer and fewer or did he not care? Maybe it was business as usual and he thought he could kill one today and then go out and kill another tomorrow or next week.

The other fellow I feel for is the zookeeper in Amsterdam who came into work on August 12, 1883 and found Jane. The last of her kind, the last of her species. (actually a subspecies, but our zookeeper wound not have known that) She would have either been dead that morning, or not been put on display and died while they were tending to her. What kind of finality would that be to feel? This is the end of the Quagga, there never will be another one.

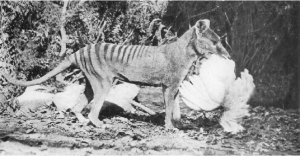

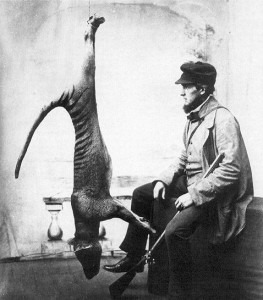

Another incident occurred in another realm of the British Empire, Australia. Specifically Tasmania. The Thylacine held on a bit longer than the Quagga. That may be said this way: Europeans arrived later in Tasmania. While the Quagga was hunted for food, skins, and to lessen competition for grazing land, the Tasmanian Tiger was hunted due to its bad reputation with farmers. The famous, or infamous, photo below was widely circulated to help encourage the removal of this ‘problem’ species.

So the farmers and settlers did their level best to protect their livestock from the dog-headed-pouched-one.

Problem was, man is a very good hunter, and eventually all the hunts, and trophies, and collections came down to this:

This here is one, Wilf Batty, who gallantly bagged the very last known wild Thylacine in existence.

There is no Thylacine Project akin to the one for Quaggas. The Tasmanian Tiger’s claim to fame has been recent “sightings” around southern Tasmania. The south is still sparsely populated and some are hopeful that the Thylacine has escaped there and remained hidden. If one is discovered that would be great, we would get to see it one more time. Finding a breeding population would be a miracle, and many are highly doubtful that it will ever happen. For now the Tasmanian Tiger has fallen not even to a realm of hope that genetics and DNA offers, but is inhabits the world of the cryptids.

Something else that is different between the two is that politics had time to get involved. Too little, too late seems to sum it up nicely. Robert Paddle’s book The Last Tasmanian Tiger: The History and Extinction of the Thylacine explains in great detail and with more clarity that I can. One point that I do want to make from this book is this: There had been a conservation movement pressing for thylacine protection since 1901. This cause was lead mostly due to it becoming increasingly difficult to obtain specimens for overseas collections. Political difficulties prevented any protection from coming into force until 1936.

Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on July 10, 1936, 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.

In fact, the Thylacine unfairly bridges the gap within the cryptozoology world between true cryptids that are not known to have ever existed, (or with some existed into modern times coexisting with mankind) and those that humans have seen (helped) off the planet. Maybe that is the draw.

Fun coincidence if you noticed in the photographs, the Quagga’s head is striped while the rear of the Tiger is. Maybe human being hate strips. Morphologically the Thylacine is interesting too, both sexes have a pouch. The only other marsupial that does is the water opossum. The tiger’s pouch is also reversed compared to other marsupials. Their pouch faces the rear and not the head as it does on a kangaroo.

Back to the stripes thing, there is a species that still exists and it might not be as endangered as you might think. I will talk more about the Okapi in the next post, how it was discovered and how that even links into my circus studies. Pygmies are involved.

Photos were ripped lovingly from wikipedia.org.