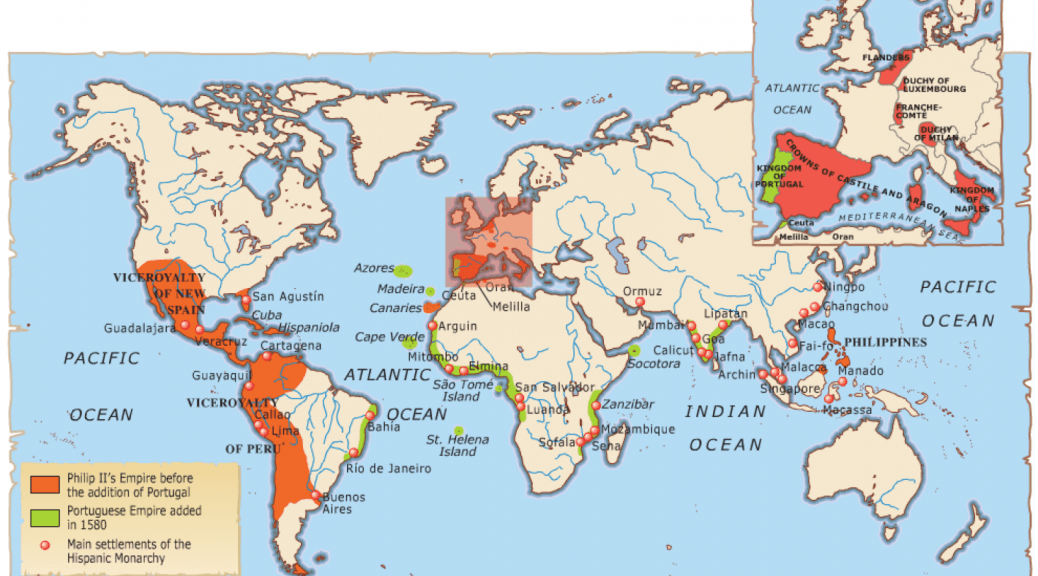

The discipline of History of Science, Technology, and Medicine has began to pride itself on the inclusion of non-western narratives in their classical antiquity sector. By this I mean to say the inclusion of Arabic sources and Islamic scientists. Some of those same people still completely ignore 1/3 of the European continent when they shift to the categorical “Early Modern” period. By extension this oversight leaves out an enormous wealth of source material dealing with the western hemisphere and the landholdings of the Iberian empire (I am using this term to include Spain and Portugal as a single unit).

What Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra does in Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World is collect a series of his essays and articles published in various journals into a single handbook of why not to ignore Iberian scientific history.

Each chapter covers a specific period or genre of Iberian scientific involvement from highlighting the chivalric narratives of Spain’s nation building and the Iberian roots of the scientific revolution to new constellations and the Bourbon revival of hard guarded imperial operations. That the book is a collection of essays is both a strength and a weakness. It is loosely connected throughout with a common Iberian genre and has been edited to remove some redundancies. It can, however, be absorbed in a few short readings or in stand-alone essays used to highlight a particular aspect of whatever class you are teaching or taking.

The mantra here is simple: if you wish to have a more complete view of the history of science in the early modern period READ THIS BOOK. There are several examples in each essay that explain the early interpretations of natural history and astrology that are “just that way” in other works on the period. Throughout chapter 2 Cañizares-Esguerra reveals that the roots of the “scientific revolution” run deep through the Iberian peninsula and even have connections to the colonial holdings of the empire. This in itself is a bit of a misnomer as he illustrates that Spain viewed her holdings in the New World the same as they did regional areas of control in places such as Italy.

After finishing the New World, New Star chapter I find it hard to believe that this section isn’t required reading for any history course looking at European astrology or astronomy. The argument that it is “fair to argue that Vespucci assigned the name ‘New World’ to the Americas largely because the skies there were populated with “stars and signs unknown to the ancients” (70) should be a huge point of contention between those claiming that the term was purposely uses to show the superiority of any inhabitants of the lands across the Atlantic. It probably will be, if people start reading more of Cañizares-Esguerra’s work. Of the new “stars and skies” the Southern Cross shows up a lot.

One of the added bonuses of this work for me was the amount of time he spends on Francisco Hernandez’s work in the new world for Spain. The University of Oklahoma History of Science collections is on the eave (6 months from) of opening an enormous multifaceted exhibition called Galileo’s World that looks at not only at Galileo (whose birthday just happens to be today) and his contributions to the world, but also the world at the time of his discoveries and experiments. One of the facets that I am helping with is the Society of the Lynx that was organized by one Frederico Cesi. There is a richly illustrated book The Eye of the Lynx by David Freedberg that highlights the society and Galileo’s involvement. One of the things Freedberg leaves out, and Canizares-Esguerra calls him on is that he fails to mention the enormous amount of Spanish backing for the publications of the society as well as the Italy province where the Cesi family lived and worked were under Spanish jurisdiction at the time.

In addition to Freedberg, Canizares-Esguerra also points out where otherwise great books by Katherine Parks, Steven Shapin, and Peter Dear are lacking in Spanish scholarship–or even mention–even though some of these books are fairly recent: Shapin and Dear being 1996 and 2001, respectively. He works methodically to tear down the “Black Legend” of Spanish backwardness and put them on at least equal footing with the rest of Europe during, and on either side of, the Renaissance.

Spain’s actions and record keeping did not do much to help their reputation. That their state secrets (and even general information) circulated in only manuscript form to keep anyone from having their information has made it more difficult for scholars to trace their true knowledge bases and sorts. Another limiting factor is ensconced within the discipline itself: language. Most of the Spanish sources are revealed and studied by Spanish scholars. This is not (only?) to follow the theme of the book with the ever-present attention to nationalism, this is because Spanish is not of the “recommended” languages of study in the discipline of history. I had to petition the university/department to have my years of Spanish count as one of my two requirements for the PhD. German and French are the usual suggestions. No wonder scholarship is so slow to catch up with the Spanish influence: the source material is difficult to find and only a small fraction of trained historians can even read them. If this book does nothing else it should at least serve as a pointed reminder of how we as a discipline are failing it by the very biases we are trying to prove we don’t have.

A final thought as I move to work on what we will display with the Hernandez connection in Galileo’s World is one of the most striking (in a book full of striking observations) revelations regarding the interpretation of natural history. Throughout this period and well into the “modern” one, the idea the New World being a place filled with degenerate beings and holding the power by climate and stars (as revealed here) to transform its inhabitants may have been the cause for some of the most monstrous accounts of animal life in Hernandez’s and others’ works. Specifically evidence of the American bison and the South American llama show obvious signs of degeneration in the new world from their predecessors–the bull and the camel–in the old. I now think that this is part of the reason such animals are depicted rather grotesquely in the woodcuts when other animals are so richly detailed and true to life.

A final note on the timeliness of reading this book: A recent Smithsonian Magazine article revealed that the extensive industrialization (silver mining et al.) of Peru after the Spanish conquest altered climate. If you have that sort of capacity to change the world, you think you would warrant a little more extensive (and intensive) historical study.