Jim Endersby published the aptly titled Imperial Nature in 2008. The book is an absolute delight to read which is one of the reason it has taken so long to get a post up. It is a book that is so interesting that you simply cannot scan through for the high points. My penchant for word play heightens the enjoyment of the title. At first glance it may mean simply nature that belongs to the Empire, but deeper within you will find that this type of botanizing (and science methodology, actually) is part of the nature of the Empire as well.

The book’s subtitle Joseph Hooker and the Practice of Victorian Science reveal the hook on which an intriguing argument takes place. the younger Hooker’s (Joseph being the son of William) career path provide a case study in which to map the expansion of science as a profession, that is something “professed,” as Endersby points out, as well as the low side of the curve for gentlemanly pursuits of scientific inquiry for interests sake, or the gentleman hobbyist as it where. Having spent considerable time on this subject myself through the analysis of the Piltdown Affair it is refreshing to see that my own experience and thinking about that particular system are not idiosyncratic or singular.

Endersby separates the aspects of the new scientific climate into chapters on subjects like “collecting, “publishing,” “corresponding,” “seeing,” and other narrow bits of methodological shaping–all the while reminding readers that these are separated for clarity, and not because they acted independently of one another in practice.

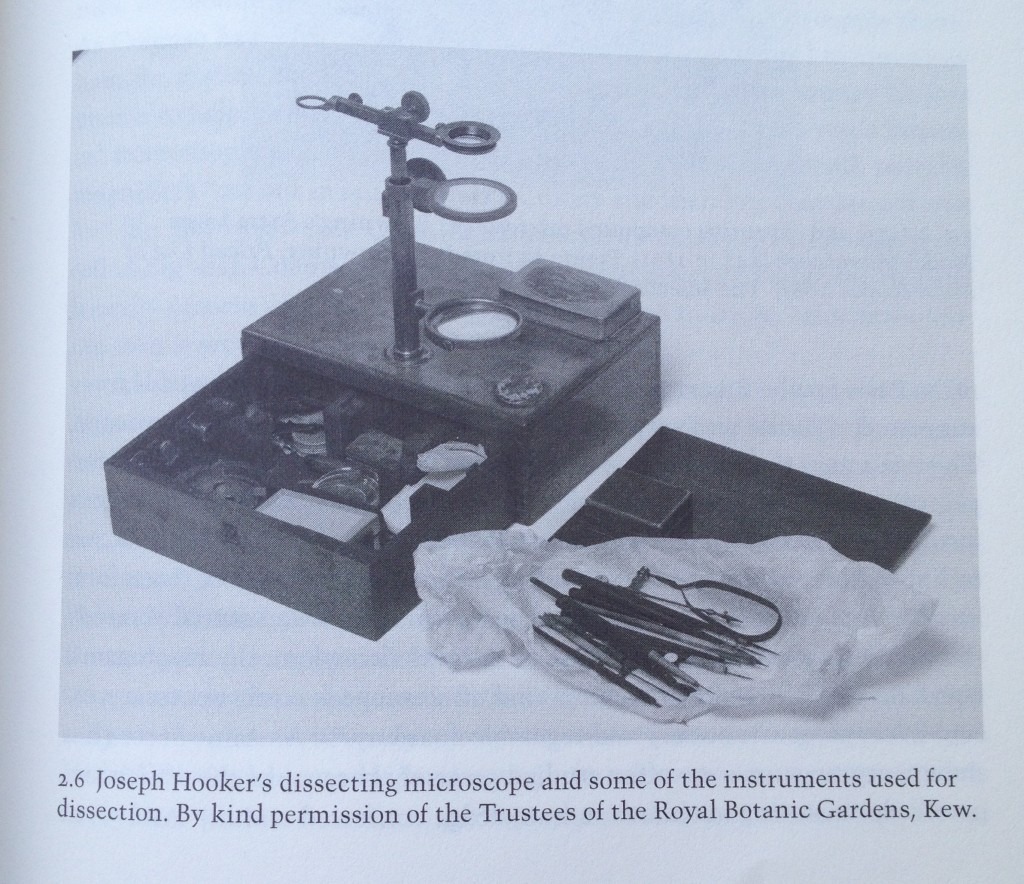

The struggle for authority between the metropolitan scientist (Hooker) and his colonial collectors (Colenso in New Zealand and Gunn in Australia) is the best part of this book. Here is one of the finest examples of exploring the relationship not only between who gets to “do” science, but who also has the authority to create scientific knowledge. Hooker needs well trained collectors (especially ones he does not have to pay) but he also needs to remain aloof enough to exert his botanical knowledge over their “idiosyncratic” and often misinterpretations in naming separate species. He, after all, is poised on top of the world looking down on creation, as the song goes, with the largest herbarium collection at his disposal (no less than Kew Gardens) to make varied and broad conclusions where his local collectors could not. To twist an old cliche Colenso was missing the herbarium (the forest) for the flowers (trees).

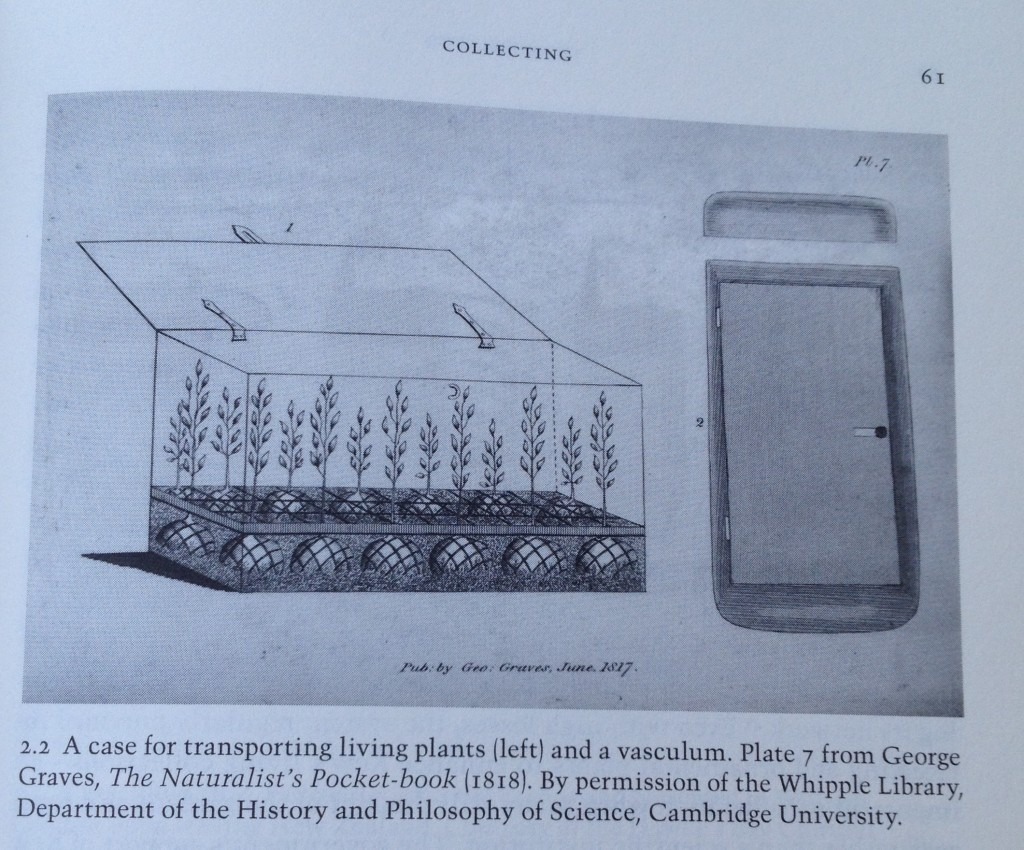

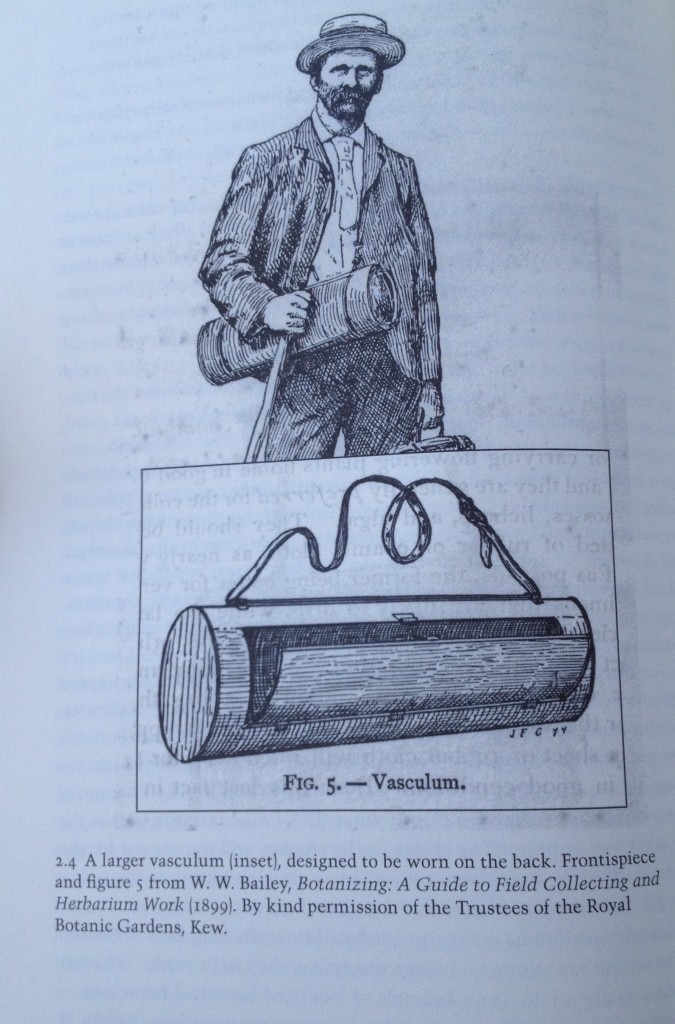

The trade network revealed here should serve as a model for anyone studying scientific relationships between any central power and periphery. The colonial collectors required adequate tools to provide Hooker with adequate specimens, so the latter may send gift of books, collecting paper, or even a highly prized microscope in order to maintain congenial relationships. In return the gentleman Gunn and the missionary Colenso continued to work hard at their collecting.

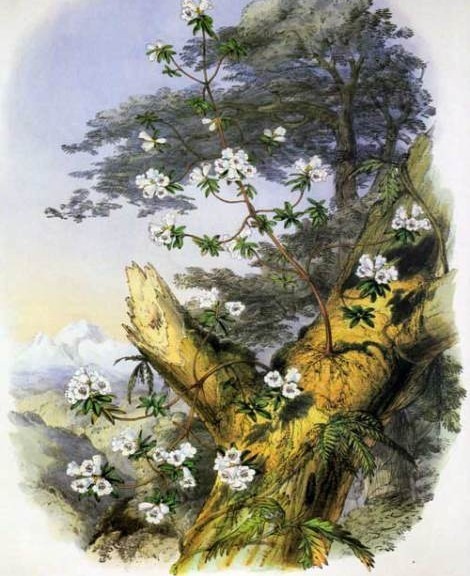

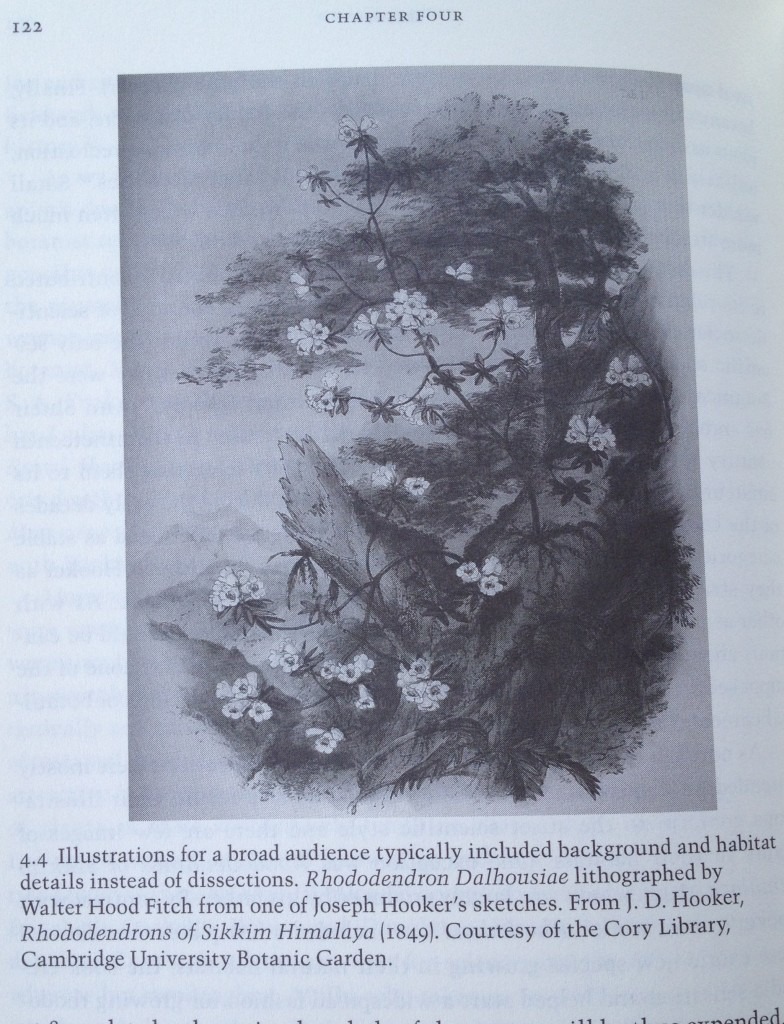

If there ever was a single book that provided a shining example of the relationship between science and art it is certainly this one. The discussions of drawing as a way to see should be part of any curricula not only at the university level, but down the the beginning of formal education, and would parents would not be remiss to utilize it before then. There is even a nice comparison between the painters of landscape vs. the botanist illustrators as well as a nuanced inclusion of the many (many) women who were involved in this particular aspect of the science. That itself should provide an avenue to explore gender in the historical context as it occurred and not just as a checkbox to make sure we are including the big three in every single thing we write. (That is, race, class, and gender–which in practice usually is only the big two of race and gender with class being ignored or, worse, broken down in terms of race).

Many in the profession of science, and probably most people in general, will take the standardization of science for granted. Standardization is something so integral to modern science that it surely would have been the basis for all historical sciences, especially those that were created by exacting Victorians. Imperial Nature reveals that is not only the case in botany, but proves the general rule for most disciplines. Systematics, labeling, descriptions, and even the plants themselves were all up for debate with different players choosing different methods and fighting for the most disciples in order to claim superiority. That is all here as well.

The book is at once incredibly readable and thoughtfully heady. I venture to guess that this is in no small part by Endersby’s professional relationship with his former supervisor James Secord. It is, however much praise I can heap upon it, not without some (more than) slight annoyances. First and foremost is the constant self reference to what is coming up. “I shall explore further,” “in chapter x,”, “below”, “which I will explain later,” and similar asides are in there enough to break the readability enough to be annoying.

Secondly, for a book about Joseph Hooker making it on his own into a paid science position, it talks much about his father’s position and his friends which acted as patrons young Joeseph’s early (and even later) exploring career. While the premise is these relationships got the young man started, the reliance and continued influence of this old system all but cuts the legs from Hooker being a good type specimen for the “new” Victorian Scientist.

A final bit of recurrence that was enough to be evident (that I will include here to bother my professor) is the constant appearance of Darwin (sorry Piers). Now, before Darwinians get defensive here (too late, I know) I understand why this is part of the story. I am fully aware of the relationship, correspondence, and support Darwin received from Hooker, but to start a book subtitled about a particular man by recounting how that man first met Charles Darwin is a little grating. I don’t think it was disingenuous but it wasn’t where I was expecting it to go. As it developed from there the narrative went something along the lines of Joseph Hooker was making a way for himself and doing things on his own–here are the various and sundry ways that his father’s influenced helped him do those things. I started counting the number of times his father’s help was mentioned only to stop after the number of Darwin references began to outnumber them.

That being said, and losing any favor from the Darwinists, this book should be required reading in a general survey that covers any aspect of Victorian Science. As it also continuously compares the emerging professional botanists with the amateur flower lovers and casual gardenists I believe it also serves well to illustrate modern concerns between professional and amateur “science” and especially collecting. It may be my particular background in paleontology that keeps this dichotomy continuously in my view, but with Endersby’s work I can most definitely see the seeds (History of Botany never wants for bad puns) of collecting debates of the 1890s and throughout the 20th century. Not only that, but going a step beyond amateurs collecting for science and into the world of “professional” collectors for profit gives yet another solid base conversation starter regarding modern fossil collectors outside the establishment.

For fun, and really because Imperial plants, and it’s The Tick, here is an episode featuring one of the best villains ever: El Seed: “Army of corn, lend me your ears…”